Post-Treatment Lyme Disease (PTLD) affects 14% of treated patients—leaving them with debilitating fatigue, pain, and cognitive dysfunction despite appropriate antibiotics. Recent breakthrough brain imaging research from Johns Hopkins reveals why: measurable white matter abnormalities and neuroinflammation persist long after infection clears. Emerging evidence shows that personalized, fMRI-guided neurorehabilitation can address the brain dysfunction driving these symptoms. This represents a fundamental shift from treating the infection to treating its lasting neurological impact—offering hope to the estimated 2 million Americans living with post-Lyme symptoms.

PTLD represents one of medicine's most frustrating challenges. Patients complete recommended antibiotic treatment, the infection clears, yet debilitating symptoms persist for months or years. The problem isn't persistent infection in most cases—it's what the infection left behind: dysregulated immune responses, inflammatory debris accumulation, and measurable changes to brain structure and function. Understanding this distinction is critical to finding effective treatment.

What is Post-Treatment Lyme Disease and how common is it?

Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS or PTLD) occurs when patients experience persistent symptoms lasting six months or longer after completing standard antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease. The CDC and Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) define PTLD by three core symptoms: severe fatigue, widespread musculoskeletal pain, and cognitive difficulties, including memory problems, concentration issues, and the notorious "brain fog."

The statistics are sobering. A rigorous 2022 prospective study from Johns Hopkins found that 14% of patients developed PTLD even with ideal early treatment—compared to just 4% in healthy controls experiencing similar symptoms. This wasn't a study of late-diagnosed or inadequately treated patients. These were individuals who received textbook-perfect care: early diagnosis, prompt antibiotic treatment, appropriate duration. Yet more than one in seven still developed chronic, debilitating symptoms.

The national impact is staggering. With approximately 476,000 Lyme disease cases diagnosed annually in the United States, this translates to roughly 47,600 to 95,200 new PTLD cases every year. Current estimates suggest around 2 million Americans are living with persistent post-Lyme symptoms, struggling with a condition that has no FDA-approved treatments and limited understanding from the broader medical community.

PTLD is distinct from "chronic Lyme disease"—a term the CDC explicitly discourages because it implies ongoing bacterial infection. In PTLD, antibiotics have successfully eliminated the bacteria, but symptoms persist due to the infection's lasting effects on immune function, inflammation, and brain structure.

The devastating cognitive symptoms nobody talks about

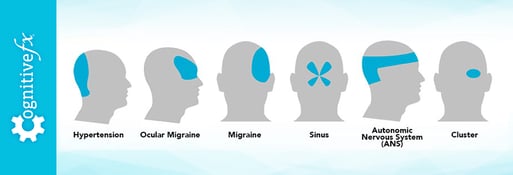

While fatigue and pain dominate PTLD discussions, cognitive dysfunction (brain fog, memory issues, difficulty concentrating)may be the most disabling symptom—and the one that receives least attention from traditional treatment approaches. Johns Hopkins research found that 92% of PTLD patients report cognitive complaints, with symptoms severe enough to significantly impact work, relationships, and quality of life.

The cognitive symptoms of PTLD include memory impairment (particularly short-term memory), difficulty concentrating for extended periods, slowed information processing speed, word-finding difficulties, problems with executive function and planning, and the pervasive "brain fog" that patients describe as thinking through cotton. These aren't subtle changes. PTLD patients score significantly below population norms on standardized quality of life measures, with impairment comparable to multiple sclerosis and other serious chronic illnesses.

What makes these cognitive symptoms particularly frustrating is their invisibility. Physical exam findings are typically minimal. Routine laboratory tests come back normal. Patients look fine to outside observers, yet struggle to perform basic cognitive tasks that were once effortless. Many report that doctors dismiss their complaints as anxiety or depression, when in fact measurable brain dysfunction is driving their symptoms.

Your brain on PTLD: What imaging reveals

For years, PTLD patients were told their cognitive symptoms were "all in their head" in the dismissive sense. Groundbreaking research from Johns Hopkins University has proven that PTLD symptoms are indeed in the head—but in the most literal, measurable, and treatable way possible.

The 2022 Johns Hopkins fMRI and DTI study represents a watershed moment in PTLD research. Using advanced functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), researchers examined the brains of 12 PTLD patients compared to 18 healthy controls while performing working memory tasks. The findings were unequivocal: PTLD patients showed unprecedented white matter abnormalities in the frontal lobe—brain regions critical for cognitive function.

Three novel activation regions appeared in white matter (typically only gray matter activates during cognitive tasks). PTLD patients showed hypoactivation in expected brain regions with compensatory activation in alternative areas—suggesting the brain was working harder through different pathways to achieve the same results. Response times were significantly slower, though accuracy was maintained. Most importantly, white matter integrity correlated directly with symptom severity: higher axial diffusivity was associated with fewer symptoms, potentially representing healing or compensation mechanisms.

Earlier Johns Hopkins research using PET scanning found widespread neuroinflammation across eight different brain regions in PTLD patients. Specifically, activated microglia and reactive astrocytes—hallmarks of ongoing brain inflammation—were significantly elevated compared to controls. This wasn't subtle. The mean difference in inflammatory markers was 0.58 standard deviations between groups, providing objective evidence that PTLD involves persistent neurological inflammation long after the bacterial infection resolves.

These imaging studies fundamentally validate patient experiences. The cognitive difficulties aren't psychological. They're neurological. The brain fog isn't imagined. It's measurable dysfunction in specific brain regions. And critically, if the dysfunction is localized and measurable, it may be targetable with the right therapeutic approach.

Why traditional PTLD treatments fail

Current medical guidelines from the CDC and IDSA provide no specific treatment recommendations beyond symptomatic management. This therapeutic vacuum leaves both patients and physicians frustrated, often leading to extended antibiotic regimens despite mounting evidence that this approach doesn't work.

The antibiotic controversy represents one of medicine's most contentious debates. Multiple rigorous randomized controlled trials—including the Klempner trials (2001) and the European PLEASE trial (2016)—consistently showed that extended antibiotic therapy provides no benefit over placebo for PTLD symptoms. The PLEASE trial found no additional benefit from 12 weeks of doxycycline or clarithromycin-hydroxychloroquine after initial ceftriaxone treatment, while 73.2% of patients in antibiotic groups experienced adverse events. A 2024 systematic review of eight randomized controlled trials concluded that antibiotics show "no effect regarding quality of life, depression, cognition, and fatigue whilst showing more adverse events."

The adverse events aren't trivial. Extended antibiotic use significantly increases risks of antibiotic-resistant infections, C. difficile colitis (including fatal cases), intravenous line complications including sepsis, and electrolyte imbalances requiring hospitalization. These risks must be weighed against the lack of demonstrated benefit.

Why don't antibiotics work for PTLD? Because PTLD isn't caused by persistent viable bacteria in most cases. Rigorous studies using xenodiagnosis (allowing uninfected ticks to feed on patients) fail to recover live spirochetes. The problem isn't ongoing infection—it's the aftermath. Recent breakthrough research from Northwestern University, published in Science Translational Medicine in 2025, identified persistent peptidoglycan fragments from Borrelia burgdorferi cell walls accumulating in the liver and joints long after bacterial death. These structurally unique fragments, modified by tick-derived sugars, cannot be processed normally by human tissues. They act as persistent inflammatory triggers, driving ongoing immune activation without any live bacteria present.

Additional mechanisms include immune dysregulation with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-23, CCL19), autoimmune responses where the immune system attacks host tissues through molecular mimicry, and central sensitization where the nervous system remains hyperactivated long after the initial insult. Importantly, these mechanisms don't respond to antibiotics because they're not caused by active infection.

The heterogeneity of PTLD also complicates treatment. Johns Hopkins researchers identified six distinct symptom factors and three clinically relevant patient subgroups, suggesting different underlying mechanisms may require different treatment approaches. A one-size-fits-all approach—whether antibiotics or any other single intervention—is unlikely to succeed for such a diverse condition.

The brain-based approach: Why personalized neurorehabilitation works

If PTLD involves measurable brain dysfunction—as Johns Hopkins imaging definitively shows—then the logical treatment approach is targeted neurorehabilitation addressing those specific brain changes. This represents a paradigm shift from treating a presumed infection to treating the neurological and cognitive sequelae that persist after the infection resolves.

Personalized, imaging-guided neurorehabilitation leverages three key scientific principles. First, brain imaging can identify specific dysfunction patterns in individual patients. The Johns Hopkins studies demonstrate that PTLD involves localized, measurable abnormalities in brain structure and function—particularly frontal lobe white matter and widespread neuroinflammation. These aren't diffuse, untargetable changes; they're specific regional dysfunctions that can be mapped and addressed.

Second, neuroplasticity—the brain's capacity to reorganize and form new neural connections—supports rehabilitation potential throughout life, even in chronic conditions. Research on traumatic brain injury, stroke, and other neurological conditions consistently demonstrates that targeted cognitive training induces measurable neuroplastic changes. Brain activation patterns can be modified, functional connectivity can be enhanced, and cognitive performance can improve through systematic, intensive training protocols.

Third, precision medicine approaches outperform standardized treatments for complex neurological conditions. Research on fMRI-guided transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression shows that personalized targeting based on individual brain imaging produces superior outcomes compared to standardized anatomical targeting. The principle applies broadly: when dealing with heterogeneous conditions affecting brain function differently across individuals, personalized treatment plans based on each patient's specific dysfunction patterns will outperform generic protocols.

fMRI-guided treatment for PTLD: The Cognitive FX approach

Cognitive FX has pioneered the application of advanced functional neuroimaging to guide personalized neurorehabilitation for post-concussion syndrome—and the approach is directly applicable to PTLD given the remarkable similarities in symptoms and brain dysfunction patterns.

The treatment process begins with comprehensive brain mapping. Patients undergo functional Neurocognitive Imaging (fNCI)—a specialized fMRI protocol that measures brain activity across multiple cognitive tasks. This isn't a simple "picture" of brain structure. It's dynamic functional assessment showing how different brain regions activate during memory tasks, attention challenges, and executive function demands. The imaging reveals regions of neurovascular uncoupling—areas where blood flow and neural activity fall out of sync, indicating dysfunction in the precise coupling mechanisms necessary for normal brain function.

The fNCI results are compared against a normative database from healthy controls and analyzed using sophisticated statistical algorithms to identify each patient's unique pattern of dysfunction. Some patients may show frontal lobe white matter abnormalities similar to the Johns Hopkins PTLD cohort. Others may demonstrate different regional dysfunctions. The key is that treatment is customized based on the individual's specific brain imaging findings, not applied generically.

The Enhanced Performance in Cognition (EPIC) treatment protocol targets identified dysfunctions through intensive, multidisciplinary therapy. The approach follows a Prepare-Activate-Rest cycle designed to promote neurovascular coupling restoration. The Prepare phase uses aerobic exercise and neuromuscular training to enhance cerebral blood flow and prime the brain for cognitive work. The Activate phase employs targeted cognitive therapies, neuromuscular exercises, sensory-motor integration, and occupational therapy—all calibrated to challenge the specific brain regions and functions identified as dysfunctional on imaging. The Rest phase provides adequate recovery time, essential for neuroplastic consolidation.

Treatment is intensive and accelerated—typically one week of full-day therapy—rather than extended over months. This format leverages principles of intensive neurorehabilitation that show superior outcomes to traditional once-weekly therapy models for many neurological conditions.

Post-treatment imaging provides objective measurement of improvements, showing changes in brain activation patterns and neurovascular coupling. This isn't relying solely on subjective symptom reporting; it's documenting measurable changes in brain function.

The evidence: Outcomes that matter

Published peer-reviewed research on Cognitive FX's fMRI-guided approach demonstrates compelling efficacy.

Independent validation came from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, where researchers conducted a completely independent peer-reviewed analysis of 64 patients before, during, and after Cognitive FX treatment. The study found that 69% reported fewer symptoms after treatment, with improvements in anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep problems, as well as objective improvements in vestibular-ocular and neurocognitive functioning. At six-month follow-up, improvements were sustained with higher social participation reported. A second independent analysis of the same data found 77% experienced meaningful symptom reduction.

This represents rare third-party validation in the neurorehabilitation field. Most clinics report outcomes based on their own internal data collection. The fact that independent researchers analyzed patient outcomes and published findings in peer-reviewed journals substantially strengthens the evidence base.

For PTLD patients specifically, the parallel with post-concussion syndrome is striking. Both conditions involve cognitive dysfunction (brain fog, memory problems, concentration difficulties), both show measurable brain dysfunction on advanced imaging, both fail to respond to traditional medical treatments, and both appear to involve neurovascular coupling dysfunction. The Johns Hopkins researchers studying PTLD brain imaging explicitly noted that their findings may apply to "post-acute COVID" and other post-infectious syndromes with similar symptom profiles.

Beyond PTLD: Parallels with long COVID and other post-infectious syndromes

The emergence of long COVID has brought unprecedented attention and research funding to post-infectious syndromes—and PTLD patients stand to benefit. The symptom overlap is remarkable: debilitating fatigue that doesn't improve with rest, cognitive dysfunction described as "brain fog," exercise intolerance, autonomic dysfunction, and pain that persists long after the acute infection resolves.

Neuroimaging studies in long COVID patients show findings strikingly similar to PTLD. Multiple studies using fMRI have identified lower functional connectivity in multiple brain regions, altered brain activation patterns during cognitive tasks with shift to compensatory brain regions, hypo-connectivity that correlates inversely with cognitive function and directly with fatigue, and measurable abnormalities in frontal lobe and brain stem regions linked to fatigue, cognitive problems, and other symptoms.

One University of Maryland long COVID brain imaging study concluded with a direct recommendation: "physicians should consider referring long-COVID patients for neurorehabilitation." This represents growing recognition that post-infectious brain dysfunction requires brain-focused treatment approaches.

The mechanistic parallels extend beyond symptoms to underlying pathophysiology. Northwestern's 2025 peptidoglycan persistence findings in PTLD mirror proposed mechanisms for long COVID, where viral debris and immune dysregulation persist despite viral clearance. Both conditions involve neuroinflammation, both show measurable brain changes on imaging, and both demonstrate limited response to traditional medical treatments.

This convergence suggests that effective treatments for PTLD cognitive dysfunction may also benefit long COVID patients—and vice versa. The field is moving toward recognizing post-infectious brain dysfunction as a distinct therapeutic target, regardless of the triggering pathogen.

When to consider fMRI-guided treatment for your PTLD symptoms

Not every PTLD patient needs advanced neurorehabilitation—but certain presentations strongly suggest brain-focused treatment would be beneficial. Consider fMRI-guided neurorehabilitation if you experience:

Persistent cognitive symptoms (memory problems, brain fog, concentration difficulties) that significantly impact daily function despite completing appropriate Lyme disease treatment. Failed response to standard PTLD management approaches including symptomatic treatments and extended antibiotic courses. Cognitive dysfunction that's worse than your pain or fatigue, or cognitive symptoms that prevent return to work or school. Symptoms lasting six months or longer with no significant improvement. Normal or near-normal results on routine neurological exams and standard brain imaging (MRI, CT), yet persistent debilitating symptoms.

The ideal candidate is someone whose primary disabling symptom is cognitive dysfunction rather than primarily pain or fatigue, though many PTLD patients experience all three. Brain-focused rehabilitation specifically targets the neurological aspects of PTLD—the measurable brain dysfunction shown on functional imaging. It's complementary to other supportive treatments (physical therapy for pain, sleep optimization, nutritional support) rather than mutually exclusive.

Timing matters. While neuroplasticity allows for improvement even years after symptom onset, earlier intervention may prevent maladaptive compensation patterns from becoming entrenched. The Johns Hopkins study found that duration of illness correlated with certain brain changes, suggesting the brain continues adapting (for better or worse) over time.

Addressing common concerns about imaging-guided treatment

"Is this just another unproven treatment promising false hope?" The distinction lies in published peer-reviewed evidence, independent validation, and objective outcome measures. Unlike many PTLD treatments promoted based solely on testimonials or clinic-reported outcomes, the fMRI-guided approach has published research in peer-reviewed journals and independent academic validation from Dutch researchers. Outcomes are measured objectively through repeat brain imaging, not just subjective symptom surveys. The approach is based on measurable brain dysfunction demonstrated in multiple independent studies from Johns Hopkins, not speculation about undetectable persistent infection.

"How is this different from regular cognitive rehabilitation?" Standard cognitive rehabilitation uses generic protocols applied similarly to all patients. fMRI-guided treatment customizes therapy based on each patient's unique brain dysfunction pattern revealed through imaging. Regular rehab may last months with once or twice weekly sessions. Intensive neurorehabilitation uses accelerated daily protocols shown to produce faster, more robust neuroplastic changes. Traditional approaches often lack objective measures of brain function change. This approach uses pre- and post-treatment imaging to document improvements in brain activation patterns and neurovascular coupling.

"What about the cost and time commitment?" Treatment typically requires one week of intensive daily therapy, making it more time-efficient than months of traditional rehabilitation. While costs are significant, the approach may be more cost-effective than years of ineffective symptomatic treatments, repeated doctor visits, and lost work productivity. Some patients' insurance covers functional neuroimaging and rehabilitation services, though coverage varies. The intensive format requires travel to the clinic, but one-week commitment may be more feasible than ongoing local weekly appointments spanning months.

"Will this cure my PTLD?" This is the critical question requiring honest answer: fMRI-guided neurorehabilitation doesn't "cure" PTLD in the sense of eliminating all underlying pathophysiology. PTLD is likely multifactorial—involving persistent inflammation, immune dysregulation, and potentially ongoing low-grade tissue processes. What imaging-guided treatment addresses specifically is the neurological and cognitive dysfunction component—the measurable brain changes driving cognitive symptoms. For patients whose primary disability is cognitive dysfunction, addressing this component can be transformative. For patients with predominantly pain or fatigue without significant cognitive involvement, brain-focused rehabilitation may be less relevant.

The goal is meaningful functional improvement return to work, restoration of cognitive abilities, reduction in debilitating symptoms not necessarily complete elimination of all symptoms. The evidence shows that 70-77% of treated patients experience meaningful symptom reduction that persists long-term. These are realistic, evidence-based expectations.

The future of PTLD treatment: From infection to inflammation to brain health

PTLD research is experiencing unprecedented momentum, driven partly by long COVID parallels bringing research attention and funding. The NIH announced a $16 million five-year initiative in 2023 funding five major PTLD research projects focused on immunologic biomarkers, peptidoglycan persistence mechanisms, autoantibody development, and predictive models for who develops PTLD.

Emerging treatment approaches under investigation include drugs targeting specific inflammatory pathways (FGFR inhibitors showed promise in 2024 Tulane study), monoclonal antibodies to clear persistent peptidoglycan debris, immunomodulatory approaches addressing dysregulated immune responses, and stem cell therapies with anti-inflammatory and regenerative properties. These represent exciting possibilities, but all remain investigational without clinical availability yet.

The paradigm shift already underway involves recognizing PTLD as primarily a post-infectious neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative condition rather than persistent infection. This reframes treatment from eradicating bacteria (antibiotics) to addressing lasting neurological impacts (neurorehabilitation, anti-inflammatory therapies, cognitive treatments). It shifts focus from one-size-fits-all protocols to personalized medicine based on individual pathophysiology and brain dysfunction patterns.

Brain imaging is becoming integral to this future. As functional neuroimaging technology becomes more accessible and imaging biomarkers become validated, expect wider adoption of imaging-guided treatment selection and monitoring. Imagine a future where PTLD patients routinely receive baseline brain imaging to characterize their specific dysfunction, treatment selection based on imaging findings rather than trial-and-error, and objective outcome tracking through serial imaging to adjust protocols.

The Johns Hopkins Lyme Disease Research Center launched its first two treatment trials for PTLD in 2022—a milestone for a condition long considered untreatable. These trials focus on understanding biological drivers and developing targeted interventions. As our understanding of PTLD mechanisms improves, treatments will become increasingly sophisticated and effective.

Finding specialized care and taking action

For PTLD patients struggling with persistent cognitive symptoms, several concrete steps can help:

Document your cognitive difficulties systematically. Track specific deficits (memory, attention, processing speed), their severity, and functional impact. Bring documentation to medical appointments to ensure cognitive symptoms receive appropriate attention alongside pain and fatigue.

Seek evaluation at specialized centers familiar with post-infectious neurological dysfunction. Johns Hopkins Lyme Disease Research Center offers clinical evaluation, though availability may be limited. Neurorehabilitation centers with functional neuroimaging capabilities can assess whether imaging-guided treatment is appropriate. For patients considering Cognitive FX specifically, consultation can determine if your presentation fits their treatment model.

Consider clinical trial participation. Johns Hopkins and other institutions conduct PTLD treatment studies. Participation provides access to cutting-edge interventions while contributing to research advancing the field. Visit ClinicalTrials.gov and search "post-treatment Lyme disease" for current opportunities.

Optimize foundational health factors. While not addressing underlying PTLD mechanisms, good sleep hygiene, appropriate nutrition, stress management, and gentle graduated exercise support overall brain health and may enhance response to targeted treatments.

Connect with support communities. Organizations like Global Lyme Alliance, Bay Area Lyme Foundation, and Johns Hopkins Lyme Disease Research Center offer patient resources, research updates, and community connections. Living with chronic symptoms is isolating; community support matters.

The bottom line

Post-Treatment Lyme Disease traps hundreds of thousands of patients in a medical limbo cleared of infection but far from well, validated by recent research but failed by current treatments. The breakthrough recognition that PTLD involves measurable, localized brain dysfunction finally explains why cognitive symptoms persist and, critically, points toward effective solutions.

Traditional PTLD treatment has focused on an infection that's no longer there—hence the consistent failure of extended antibiotics. The future lies in addressing what the infection left behind: neuroinflammation, altered brain connectivity, and neurovascular coupling dysfunction that persists long after Borrelia burgdorferi has been eradicated.

For the significant subset of PTLD patients whose lives are defined by cognitive dysfunction the brain fog, memory problems, and concentration difficulties that prevent work and normal life—personalized, fMRI-guided neurorehabilitation offers something previous approaches haven't: evidence-based treatment targeting the actual measurable dysfunction rather than chasing bacterial ghosts.

The convergence of PTLD brain imaging research from Johns Hopkins, outcomes data from intensive neurorehabilitation programs, and parallel findings from long COVID studies creates a compelling scientific foundation. Brain dysfunction is real, measurable, and most importantly potentially reversible with the right approach.

This doesn't mean PTLD is "solved" or that every patient will respond to any single intervention. PTLD remains complex and heterogeneous. But for the first time, patients struggling with post-Lyme cognitive symptoms have a treatment approach grounded in objective brain imaging, supported by published peer-reviewed research, validated by independent investigators, and offering realistic hope for meaningful, sustained improvement.

The question shifts from "Why won't this infection go away?" to "How do we restore normal brain function after the infection's impact?" That's the question imaging-guided neurorehabilitation is designed to answer.

Objective brain imaging validates your experience. No more being dismissed or told it's psychological. We show you exactly what's wrong with your brain function and track measurable improvements.

One intensive week, not months of ineffective treatments. Our EPIC protocol delivers concentrated, daily therapy proven more effective than traditional once-weekly approaches. You invest one week, not endless months.

Treatment backed by published research. Unlike most neurorehabilitation clinics relying solely on testimonials, our approach has peer-reviewed published outcomes and independent academic validation.

Are You a Good Candidate for fMRI-Guided Treatment?

You may benefit from our approach if:

✓ Cognitive dysfunction (brain fog, memory problems, concentration difficulties) is significantly impacting your daily life

✓ You completed appropriate Lyme treatment but symptoms persist 6+ months

✓ Extended antibiotics and other treatments have failed

✓ Cognitive symptoms prevent you from working, studying, or living normally

✓ You want objective evidence of what's wrong—and proof that treatment is working

Take the First Step: Free Consultation

You've been struggling long enough with a condition most doctors don't understand.

Our team specializes in post-infectious brain dysfunction. We understand PTLD because we've treated it. We can see the brain changes driving your symptoms. And we have evidence-based protocols that work.

Schedule your free consultation to discuss:

- Whether your symptoms fit our treatment model

- What to expect from fNCI brain imaging

- How our one-week intensive EPIC protocol works

- Realistic expectations based on your specific presentation