Long-Term Anxiety After a Concussion | CognitiveFX

There is a whole world of hurt and pain for patients who experience mental health symptoms after a concussion. Not all of them realize that concussions can cause anxiety, and those who do know it...

Published peer-reviewed research shows that Cognitive FX treatment leads to meaningful symptom reduction in post-concussion symptoms for 77% of study participants. Cognitive FX is the only PCS clinic with third-party validated treatment outcomes.

READ FULL STUDY

It should come as no surprise that COVID-19 — both the illness itself and all the situational changes that come with the coronavirus pandemic — is messing with our minds. Many people are experiencing heightened anxiety in response to the pandemic, and not just people who have experienced anxiety before.

You may feel like you can’t get through the day without checking the news on COVID ... several times. You may feel restless and find it difficult to work, instead finding yourself scrolling Facebook endlessly. Thoughts of “What if ... ?” may keep you from falling asleep at night. You may be snippy with family members due to a near-constant feeling of frustration.

So why do we feel this way? All these reactions stem from how your body identifies and responds to a perceived threat (and you can bet that COVID-19 is one of them!). For simplicity’s sake, we’ll call it your body’s threat response system, which has three prongs: the fear prong (the “flight” response), the anxiety prong (the response to prepare for potential, future challenges), and the anger prong (the “fight” response).

All three of these prongs can be present and affect your moods and decision-making during the pandemic. We’ll cover what each one does and why it might be overactivated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and then we’ll discuss some ways to help those systems calm down (especially the anxiety prong).

Finally, since we specialize in treating post-concussion patients whose symptoms haven’t resolved with time, we’ll dedicate a section to explaining why you’re more likely to have an overactive threat-detection system after suffering a concussion and discuss some concussion-specific scenarios.

(When the anxiety prong of the threat response system in your body is constantly elevated, we refer to that as generalized anxiety disorder. This post doesn’t cover generalized anxiety disorder, although you may still find some of the content helpful if you suffer from it.)

Just so you know, our specialty is treating patients with lingering symptoms from concussion or another source of brain trauma. If that’s you or someone you know, schedule a consultation to help you plan your recovery.

Note: Any data relating to brain function mentioned in this post is from our first generation fNCI scans. Gen 1 scans compared activation in various regions of the brain with a control database of healthy brains. Our clinic is now rolling out second-generation fNCI which looks both at the activation of individual brain regions and at the connections between brain regions. Results are interpreted and reported differently for Gen 2 than for Gen 1; reports will not look the same if you come into the clinic for treatment.

Our innate threat response system has three prongs: fear, anxiety, and anger. It’s designed to protect us; the reactions we have on account of them are normal and part of what makes us human.

In this section, we’ll explain how each works, using COVID-19 as the backdrop for understanding them. Afterward, we’ll explain how the system that’s designed to help us manage threats gets a little too vigilant.

The fear prong is what we use to deal with immediate, pressing threats. Most people won’t experience it during the COVID-19 pandemic, but if you or a loved one actually gets infected with COVID, then you might experience a full-blown fear response.

The fear prong results in physiological (i.e., bodily) changes such as clammy palms, a racing heart rate, and increased or abnormal breathing. It can also manifest an intense desire for resolving the issue or feeling like you need to flee. It typically focuses our attention on that one thing we’re reacting to in the moment.

For upcoming or potential threats, our bodies rely on the anxiety prong. It’s future oriented, trying to help us prepare for what could harm or challenge us down the line.

Physiological changes are less pronounced than in the fear response: You could experience it as a clenched jaw, tight neck muscles, or perhaps some abdominal discomfort. Behaviorally, it feels like you’re constantly preparing.

Anxiety might lead you to spend hours running through scenarios in your mind and playing them out, trying to make contingency plans for different possibilities. It’s supposed to motivate you to take steps to prepare or protect yourself, but when it runs amok, you’ll end up feeling fatigued, you might procrastinate a lot, and you may start to feel like you’re always worrying.

The anger prong is often a response to an immediate situation, but it can also be delayed. Anger is your body’s go-to response when you feel you’ve been offended or violated in some way. This system makes you want to stand up to the threat rather than to run away.

COVID-19 has produced significant disruption to our lives. Most people have restrictions of some kind; some are out of work; others have lost loved ones and couldn’t even be in the room to say goodbye. It would be an understatement to say times are frustrating.

Feeling angry and frustrated with what’s happening — even if it’s simply aggravation at the need for social distancing — is completely normal.

There’s an important distinction between functional worry and dysfunctional worry. Functional worry helps us plan for the future but doesn’t consume all our time, attention, and energy. Dysfunctional worry interferes when it becomes ruminative and distracts us from doing other things.

For example, knowing up-to-date information on how to protect your family from infection and staying on top of what your state or country’s rules are for going out is good.

Checking every few hours and scrolling through the news and FB before bed because you can’t get your mind off it? Not so good.

Almost everyone experiences some dysfunction in their threat response system, although some experience it more often than others. An overactive threat detection system stems from many factors: temperament, genetics, past experiences, environment, etc. Those who experience this dysfunction all the time are said to have generalized anxiety disorder.

Here’s a quick overview of the factors that can influence your likelihood to have a dysfunctional response to a perceived threat:

Often, people who are at risk for generalized anxiety disorder exhibit different beliefs about their worry than people who are able to keep their anxiety in check. They view worry as something they need to do and see it as more helpful than their counterparts.

Worrying feels productive to them; but eventually, this leads them even to worry about worrying, once they realize it’s taking up so much of their time and energy. You might find yourself wondering, “What’s wrong with me?” or perhaps, “Oh no, I’m worried about ‘X’; I’m going to lose control of my worry cycle and be unable to do what I need to do.”

Conversely, people who don’t develop generalized anxiety disorder typically don’t hold those strongly positive or strongly negative views about worry. If you do hold stronger views about worry, they may be influencing the severity of your anxiety.

Just so you know, our specialty is treating patients with lingering symptoms from concussion or another source of brain trauma. If that’s you or someone you know, schedule a consultation to help you plan your recovery.

So... how do you talk your threat response system down when it’s causing you problems? Here are a few things that have helped our anxiety patients.

Note: Whenever you’re planning for your family’s safety regarding COVID-19, refer to trusted organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for timely information and recommendations on how to protect yourself and your loved ones.

One of the behaviors that both stems from the anxiety system and aggravates it further is checking and rechecking the thing that’s making you anxious. Your system is looking for reassurance that you’re prepared for what’s to come; checking once or twice is fine, but when it becomes obsessive, you have a problem on your hands.

For example, say you’re a student with an upcoming test. Your anxiety system pokes your attention so that you recheck the time of the test and the topics covered to make sure you’ve studied what you needed to. But you only need to check once or twice to meet the need (preparedness for the exam). If you start checking that information more frequently, it only serves to keep your anxiety system activated, making you feel worse and reducing your ability to focus on other needs.

Returning to the example of COVID-19, you might find yourself checking medical news every night before bed, then staying awake and ruminating on the topic when you’re trying to sleep, which only serves to make you feel worse.

It’s very important to set limits on “checking and rechecking” behavior. Control your exposure to whatever triggers your anxiety. If checking the news too often or obsessively scrolling social media is a problem for you, decide how often you’ll check it (once per day, or three times per week, etc.) and stick to that regimen, no matter how tempted you are to check sooner.

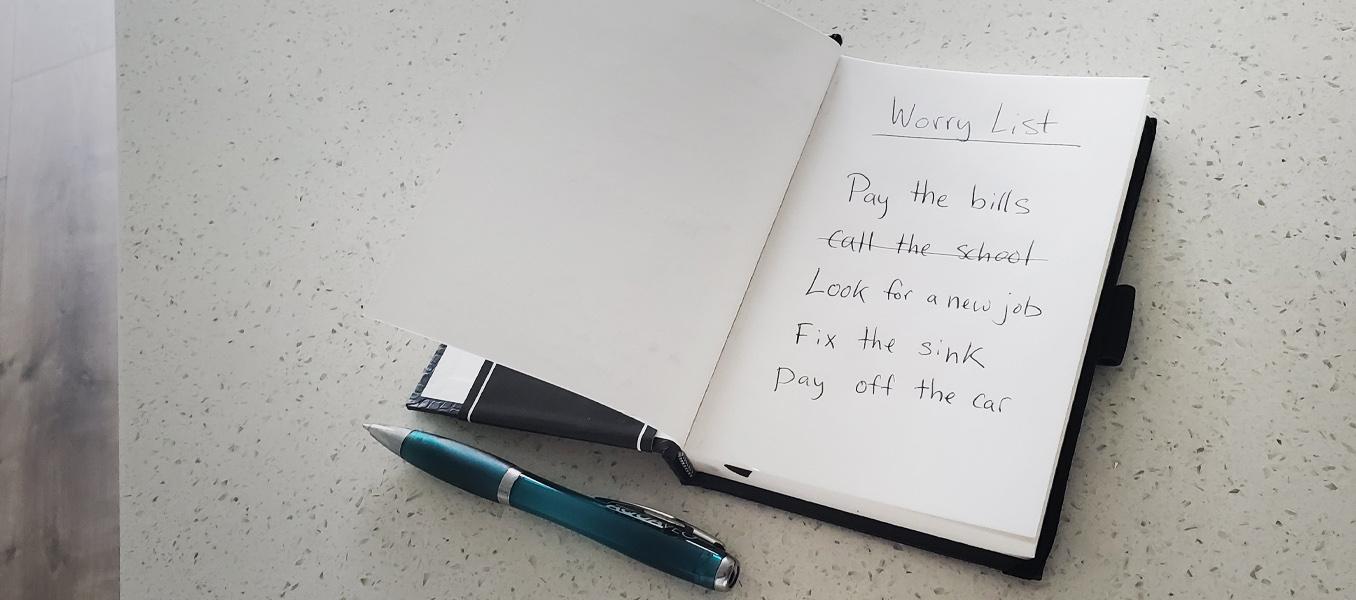

Worry time is a technique to help you learn to restrain anxious thoughts. The idea is to set aside 30 minutes each day to think all the way through one or two of your big worries. During the day, add worries to your “worry list,” then decide what you’ll tackle during that session. If a new or old worry tugs for attention, make sure it’s on your worry list, then ignore it.

So if you’re worried about getting supplies (food, toilet paper, etc.) for your family, for example, you might sit down during worry time and think through it: What if the stores run out of meat? What if I can’t find toilet paper? What if other supplies dwindle? Take it to the furthest extreme you have to.

Then, when you’re done, say, “OK, what can I do about it?” And if there are concrete steps you can take to mitigate risk, great! Write those down. Maybe you’ll create action items such as “Buy beans and rice,” or “Look up vegetarian recipes,” or “Research alternative proteins.”

But if the worry is something you can’t do anything more for, set the concern aside. Work on accepting that it’s not something you can change.

You’ve probably heard this advice before, but it’s worth saying again: Build a calming activity into your daily routines. You might try:

You can get creative here. The important thing is to carve out the time for a self-care routine that promotes your well-being.

With the anger response in particular, it can be easy to downplay what you’re feeling. But it’s helpful to recognize that your body and mind are responding normally to this situation. It’s okay if you need to spend some time intentionally thinking about what’s aggravating you.

For example, you might acknowledge the restrictions placed on you because of the pandemic and accept them as things you can’t change. And if the source of frustration is something you can change, that doesn’t mean you should accept it without changing it. It just means it’s still helpful to accept it for what it is, then work on changing what you can in a reasonable time frame.

Even just verbalizing your limitations and saying “I don’t like this, but I’ll accept it for now” can help you feel a bit better.

Sometimes, all it takes to break a cycle of negative thoughts in the moment is some gratitude. There are several ways you can leverage gratitude to improve your mental health:

Note: If you would like to speak with a psychologist or another licensed mental health professional, you can visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) for help finding a provider and other information. Many health providers offer telehealth visits, which means they will treat you during a video chat or phone call to protect you from the coronavirus disease. Both low risk and higher risk patients (those with underlying health conditions) can get needed help with any form of mental illness via telemedicine.

If you’re experiencing post-concussion symptoms or post-concussion syndrome, then you probably have more triggers than folks who don’t. Before treatment, many of our clients are overwhelmed by bright lights, loud sounds, and crowds. And for those who do tolerate them, they can only take so much sensory input before they’ve had enough.

The physiological reaction to overloaded senses is typically either “Get away!” or “Get me out of here!” As a result, their anxiety system gets activated more often, making it more sensitive to situational stressors such as an infectious disease outbreak. Plus, the more often you’re in a high anxiety state (and anxiety is the most common mental-health-related symptom we’ve seen in our patients), the easier it is to be triggered into another anxiety response, or even a fear response.

Another difficulty is that people with post-concussion syndrome may not be able to do some of the things that helped them relax or de-stress before their injury. They may already be dealing with additional stressors such as reduced income or lost jobs, overbearing mental and physical symptoms, social isolation, and disruption of “normal” daily life.

But coronavirus anxiety isn’t the only possible response to these difficult times. It’s also not unusual for patients to experience an anger response — post-concussion symptoms put very real and difficult limits on what you can do, which results in real grief and frustration. So, a situation such as COVID can just compound what’s already there.

In some cases, post-concussion patients develop a condition known as dysautonomia. Dysautonomia can exaggerate the physiological response to a threat; a fear response might result in dizziness and blood pressure changes, for example, or it might feel like a panic attack rather than a normal scare.

Note: While we are able to assist patients with some dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, we cannot fully treat dysautonomia. We can treat the core issues behind lingering post-concussion symptoms, which often results in significant quality of life improvement for the patient.

If you’ve been suffering from anxiety about the COVID-19 outbreak, or anything else in your life, you’re not alone. Some anxiety is part of the common human experience; when it gets out of hand, you can always seek help. If you find that the strategies presented here are not enough for the severity of your anxiety, please reach out to a local health care provider who can help you with your specific needs. You do not have to suffer alone.

If you or someone you know is suffering from lingering symptoms from a concussion, COVID-19 (viruses can cause concussion-like symptoms too!), or any other source of brain trauma, please reach out to schedule a consultation. We would be happy to discuss your injury and advise you on how to proceed with recovery.

Dr. Spangler is a Clinical Psychologist with over 20 years of experience working in both clinical and academic settings. She earned her doctorate degree in Clinical Psychology at the University of Oregon followed by a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in the Department of Psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Spangler served as a Professor of Psychology at Brigham Young University for 15 years where she directed training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Clinical Psychology Doctoral Program, and conducted research on the etiology and treatment of depressive, anxiety, and eating disorders. She also served as a Visiting Professor in the Department of Psychiatry Cognitive Therapy Centre at Oxford University in England. Dr Spangler has authored over 60 publications and has lectured worldwide. She has received numerous awards for her collective work from the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Psychological Association, the International Association for Cognitive Psychotherapy, the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, the Beck Institute, and the National Association of Professional Women.

There is a whole world of hurt and pain for patients who experience mental health symptoms after a concussion. Not all of them realize that concussions can cause anxiety, and those who do know it...

Living with the lingering symptoms of a concussion for months or even years is life-changing. Patients with post-concussion syndrome (PCS) can feel worthless, misunderstood, lonely, and frustrated....

People who have suffered a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) often experience difficulties with theirpsychological and emotional health. For example, among the patients we treat at our clinic, it’s...

Living with the mental health effects of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) can be an isolating and overwhelming journey. Not all patients realize that brain injuries can cause significant emotional...

Emotions are expressed in many ways—through gestures, facial expressions, and the tone of our voice. When you're happy or upset, others typically recognize those emotions by looking at you and...

Severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), concussion (mild traumatic brain injury or mTBI), and other head trauma can cause high blood pressure, low blood pressure, and other circulatory system changes....

Published peer-reviewed research shows that Cognitive FX treatment leads to meaningful symptom reduction in post-concussion symptoms for 77% of study participants. Cognitive FX is the only PCS clinic with third-party validated treatment outcomes.

READ FULL STUDY