Persistent symptoms after a head injury (post-concussion syndrome) can be confusing. They don’t always seem like problems an injured brain should cause. Symptoms like memory problems, trouble reading, or light sensitivity make sense; your brain is closely involved in those processes.

But what about getting dizzy after exercise? Feeling nauseated? Feeling your heart race while your blood pressure stays the same?

These and other surprising symptoms often happen because your brain is intricately bound up with a crucial system that impacts nearly every organ in your body: the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

When your brain is affected by an injury, your ANS is often affected, too. Some folks experience short term dysfunction in their ANS, but for others, the ANS stubbornly refuses to correct itself.

We’ll explore why that is — and what can be done about it — in this post. Here’s the full overview:

The autonomic nervous system is complex. We regularly get questions from the patients we treat at our clinic about how it works and why it’s causing their symptoms. And because scientists have not fully discovered how the ANS is impacted by head injury, there’s a limit to what we can explain and treat.

But there are ways we can help. We can’t make you an expert on the ANS in the span of one blog post, but we hope to help you come away with new knowledge about how your injury is still affecting your body and what you can do to help it heal.

Every week, we help post-concussion patients recover from persistent symptoms. 95% of our patients show statistically verified restoration of brain function by the end of one week. To discuss your specific injury and symptoms, schedule a consultation with our team.

Note: Any data relating to brain function mentioned in this post is from our first generation fNCI scans. Gen 1 scans compared activation in various regions of the brain with a control database of healthy brains. Our clinic is now rolling out second-generation fNCI which looks both at the activation of individual brain regions and at the connections between brain regions. Results are interpreted and reported differently for Gen 2 than for Gen 1; reports will not look the same if you come into the clinic for treatment.

What Is the Autonomic Nervous System?

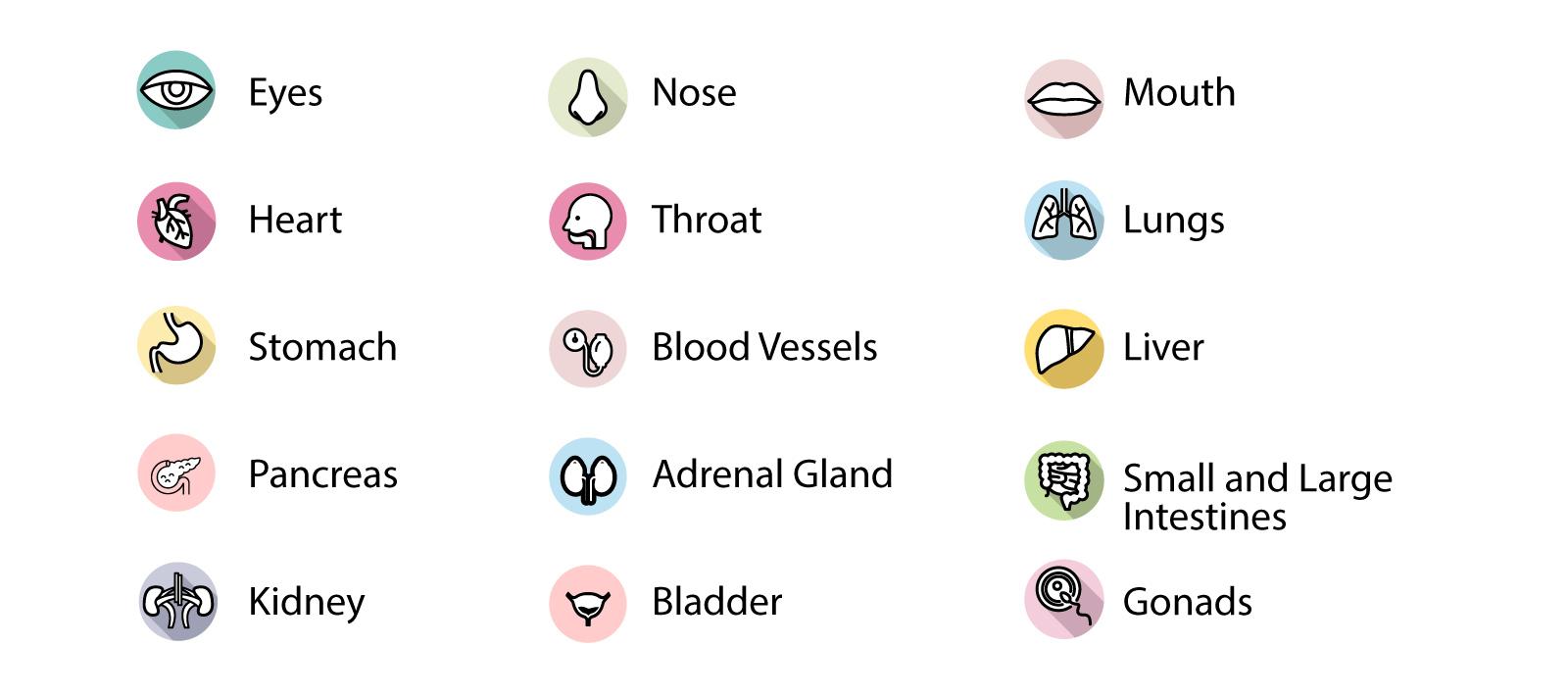

The autonomic nervous system regulates a host of involuntary processes throughout your body. Some examples include your heart rate, blood flow, breathing, digestion, and physiological threat response. It’s in charge of your “fight or flight” reaction, along with your “rest and digest” state.

The sheer number of systems your ANS affects is amazing! It’s involved with...

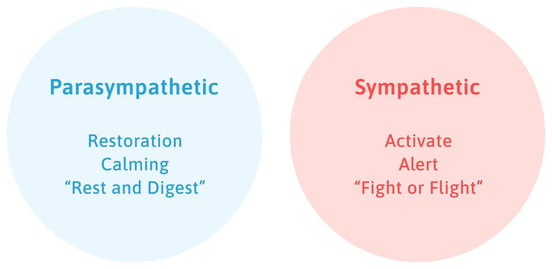

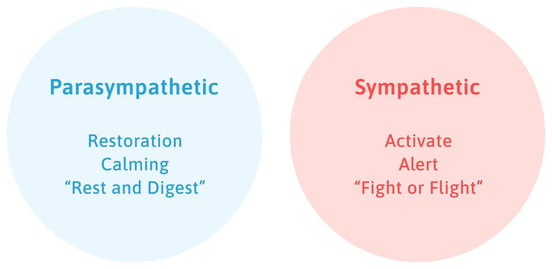

The ANS has two halves: the parasympathetic nervous system and the sympathetic nervous system. This division plays a critical role in post-concussion symptoms, which we’ll explain further in the post.

The parasympathetic system is the “rest and digest” part of the nervous system. It helps your system calm down.

The sympathetic system is the “fight or flight” part of the nervous system. It ramps up your body’s response to a perceived threat and can keep you “on edge” if it thinks you’re unsafe.

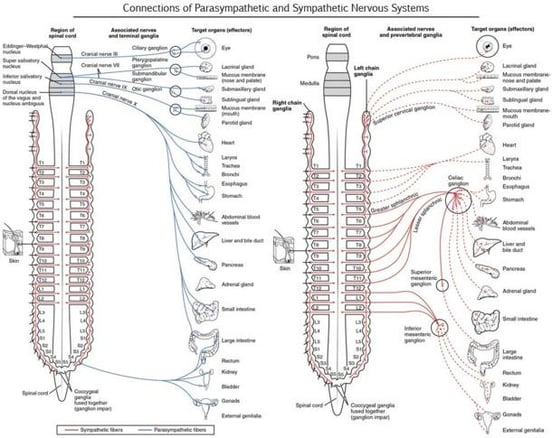

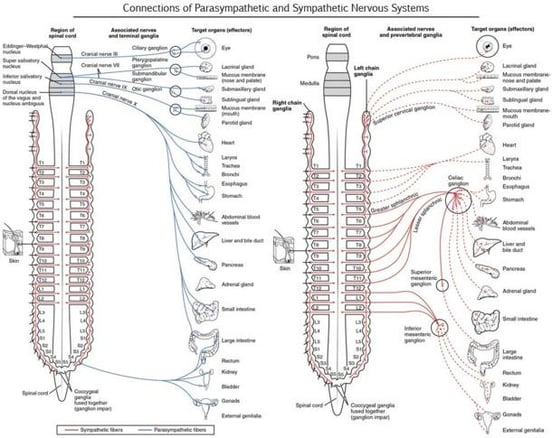

The parasympathetic system connects to other parts of your body through a handful of closely-clustered cranial nerves (nerves near the top of your spine where it joins the skull). The sympathetic system has clustered connections throughout the cervical spine. This is important: that clustering is why some sections of the ANS can become dysregulated while others are fine. When something does go wrong, clustered nerve connections are why one patient might have light sensitivity but no digestive issues, while another patient might have trouble breathing correctly but no issue with bright lights. Still others might experience all of the above.

If the nerve connections of the ANS look complicated, it’s because they are! This graphic from Diffen.com shows that the sympathetic nervous system (on the right) has segmented connections. It’s why some patients may have dysregulation that affects their digestion, but not their vision, for example.

In a healthy ANS, the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems are both in a state of flux. They balance each other throughout the day so you’re able to respond to each situation you encounter. Having the parasympathetic or the sympathetic nervous system in control too often would mean your body was ill-prepared to handle the different needs you have.

For example, you need the sympathetic system to dominate if you’re running a race. But when it’s time to calm down afterward, you want the parasympathetic system to engage more strongly.

The constant up-and-down adjustments of your nervous system are key to your wellbeing. And if that balance is disrupted by an injury, it can result in dysautonomia.

What Is ANS Dysfunction (Dysautonomia)?

Autonomic nervous system dysfunction (also known as dysautonomia) includes any problem which causes some or all of your ANS to function abnormally. It can be permanent or reversible depending on the cause. Dysautonomia can stem from many different underlying causes, including genetic and acquired disease and injury. Some of those causes include:

- Autoimmune disorders (Celiac disease, antiphospholipid syndrome, etc.).

- Genetic conditions (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Riley-Day syndrome, Sjogren’s syndrome, etc.).

- Situational factors (heavy metal or alcohol poisoning, extended bed rest, vitamin deficiency, chemotherapy, etc.).

- Other diseases (diabetes, lupus, Crohn's disease, mitochondrial diseases, etc.).

- Physical trauma (severe or mild traumatic brain injury, surgery, car accidents, etc.).

You can visit this page from Dysautonomia International for a more complete list of causes and their descriptions.

Most people have secondary dysautonomia, meaning it’s caused by some other condition that doesn’t directly damage the ANS but does dysregulate it. Primary dysautonomia — either from a condition that directly attacks the nerves or from an acquired injury to those nerves — is extremely rare. Anything that causes physical damage to the nerves in the ANS is irreversible. Aside from that, dysautonomia is often treatable — at least to a certain extent.

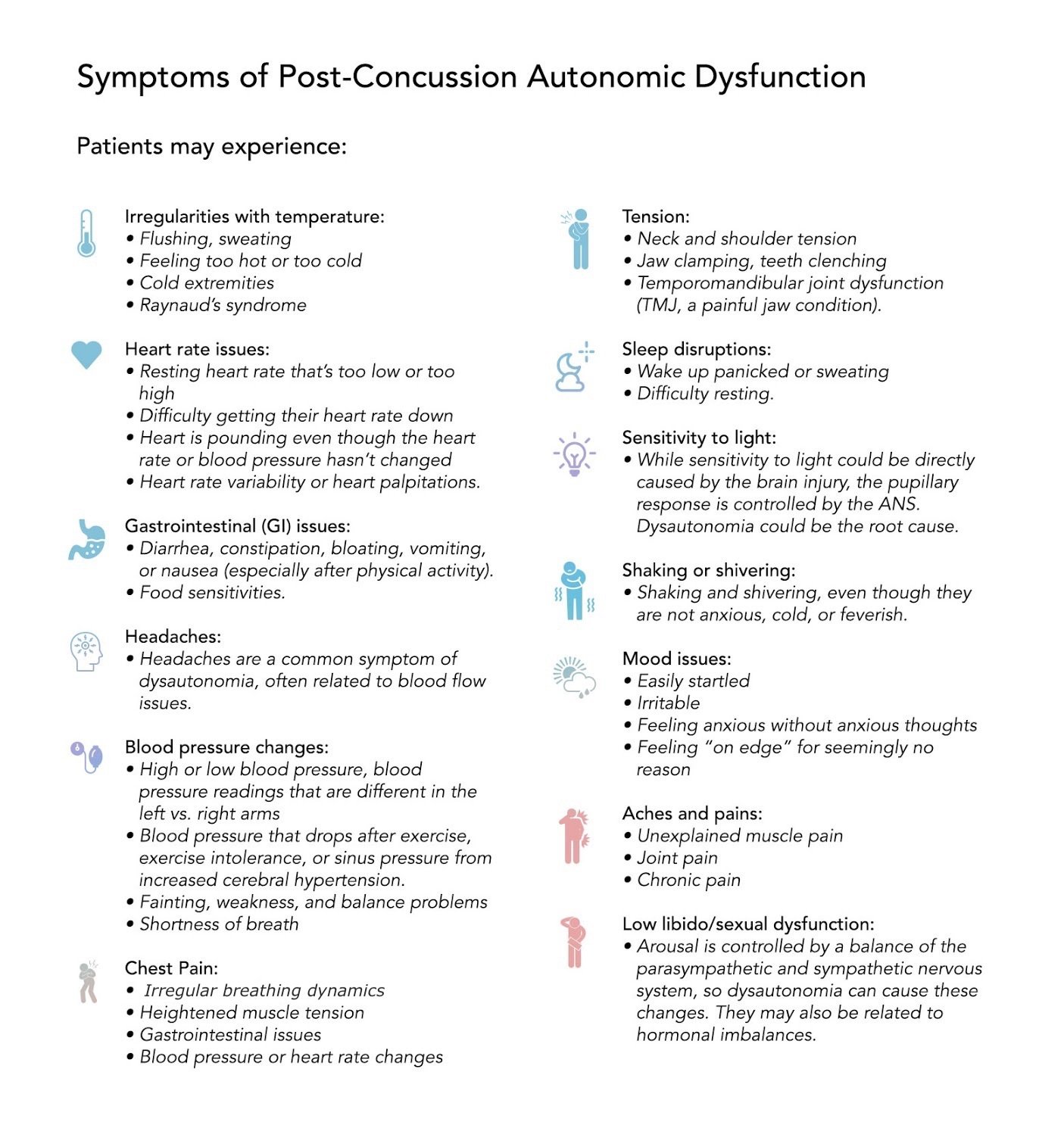

What Are the Symptoms of Post-Concussion Autonomic Dysfunction?

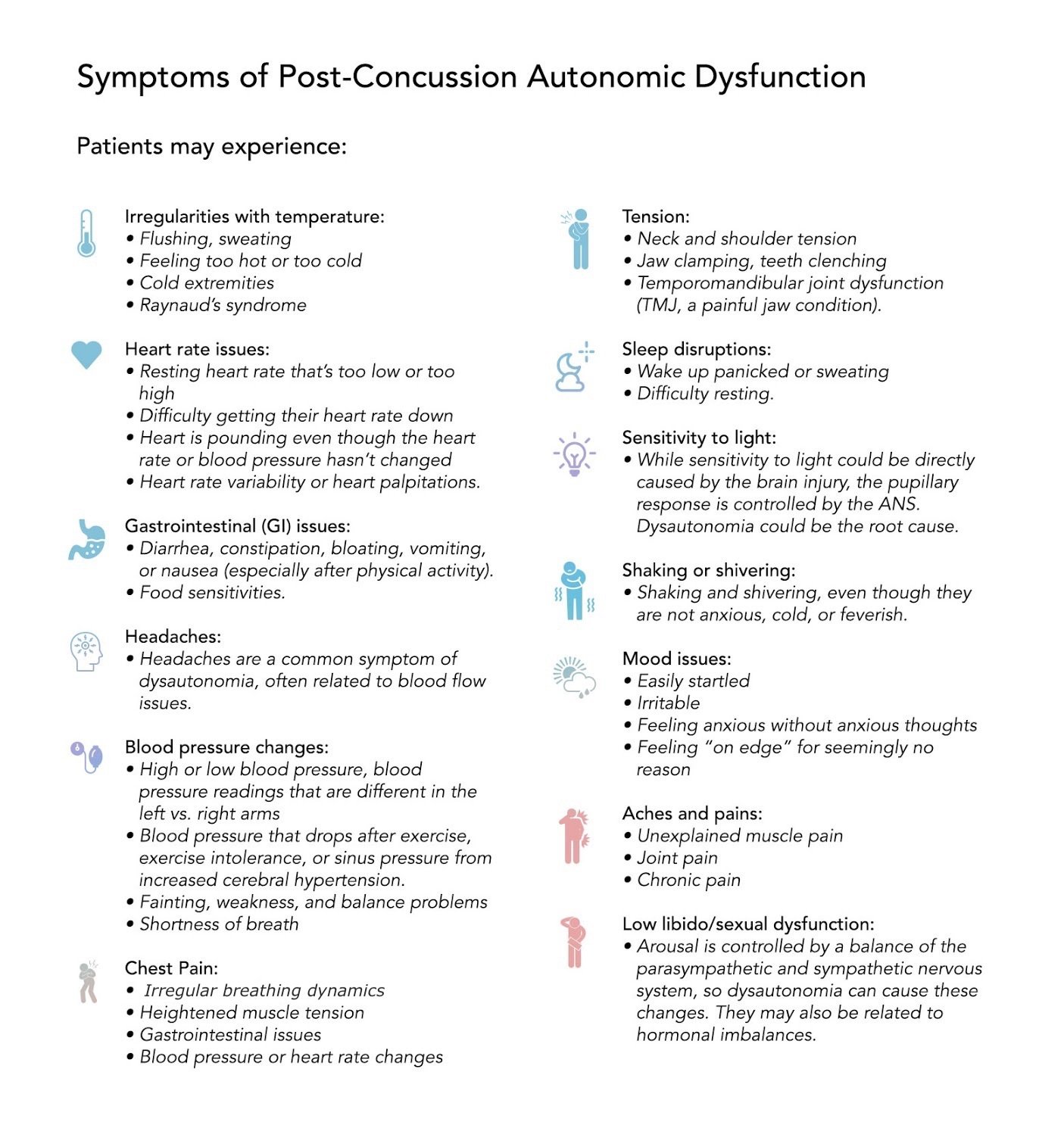

Not every patient has every symptom. Symptoms can evolve or worsen over time. They can also be affected by the other situations and conditions in your life (puberty, menopause, stress, hormone dysfunction, psychological anxiety, etc.).

Anything that adds stress or fear into your life can increase the dominance of the sympathetic nervous system. Hormones are tied closely to its functioning as well, so if you experience hormone changes, you might have symptoms of dysautonomia.

Here’s a complete list of the symptoms we’ve observed in patients. If you have concussion-induced dysautonomia, you may have any combination of the following symptoms (or some we haven’t seen before — the ANS malfunctions for every patient differently):

- Irregularities with temperature: Patients may experience flushing, sweating, feeling too hot, feeling too cold, or having cold extremities (like fingers and toes!). Some also develop Raynaud’s syndrome, in which blood flow in extremities is severely restricted when exposed to cold weather.

- Heart rate issues: Patients may have a resting heart rate that’s too low or too high, may have difficulty getting their heart rate back down to rest, may feel like their heart is pounding even though the heart rate or blood pressure hasn’t changed, may have heart rate variability, or may experience heart palpitations.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) issues: Patients with GI dysregulation may experience diarrhea, constipation, bloating, vomiting, or nausea (especially after physical activity). While the exact etiology is unknown (we suspect it’s related to system inflammation post-injury), some patients also develop food sensitivities.

- Headaches: Headaches are a common symptom of dysautonomia, often related to blood flow issues.

- Tension: Patients may experience neck and shoulder tension, jaw clamping, teeth clenching, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJ, a painful jaw condition).

- Blood pressure changes: Patients may have high or low blood pressure, blood pressure readings that are different in the left vs. right arms, blood pressure that drops after exercise, exercise intolerance, or sinus pressure from increased cerebral hypertension. They could also experience fainting, weakness, shortness of breath, and balance problems.

- Sleep disruptions: Patients may wake up panicked or sweating, or otherwise have difficulty resting.

- Sensitivity to light: While sensitivity to light could be directly caused by the brain injury, the pupillary response is controlled by the ANS. Dysautonomia could be the root cause.

- Shaking or shivering: Some patients notice themselves shaking and shivering, even though they are not anxious, cold, or feverish.

- Mood issues: Patients may find themselves easily startled, irritable, feeling anxious without anxious thoughts, or feeling “on edge” for seemingly no reason.

- Aches and pains: Some patients experience unexplained muscle pain, joint pain, or chronic pain. We’ve even seen some patients develop rheumatoid arthritis connected to their dysautonomia.

- Chest pain: This symptom can come from a number of ANS-related issues: irregular breathing dynamics, heightened muscle tension, gastrointestinal issues, blood pressure or heart rate changes, and more.

- Low libido/sexual dysfunction: Arousal is controlled by a balance of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system, so dysautonomia can cause these changes. They may also be related to hormonal imbalances.

Note: We’ve noticed many of our dysautonomic patients complain of getting sick easily. Since this is purely anecdotal, we haven’t listed it as a symptom of ANS dysfunction. Nonetheless, if you have dysautonomia and always get the latest virus or constantly have sinus infections, there might be a connection.

How Does a Concussion Affect the Nervous System?

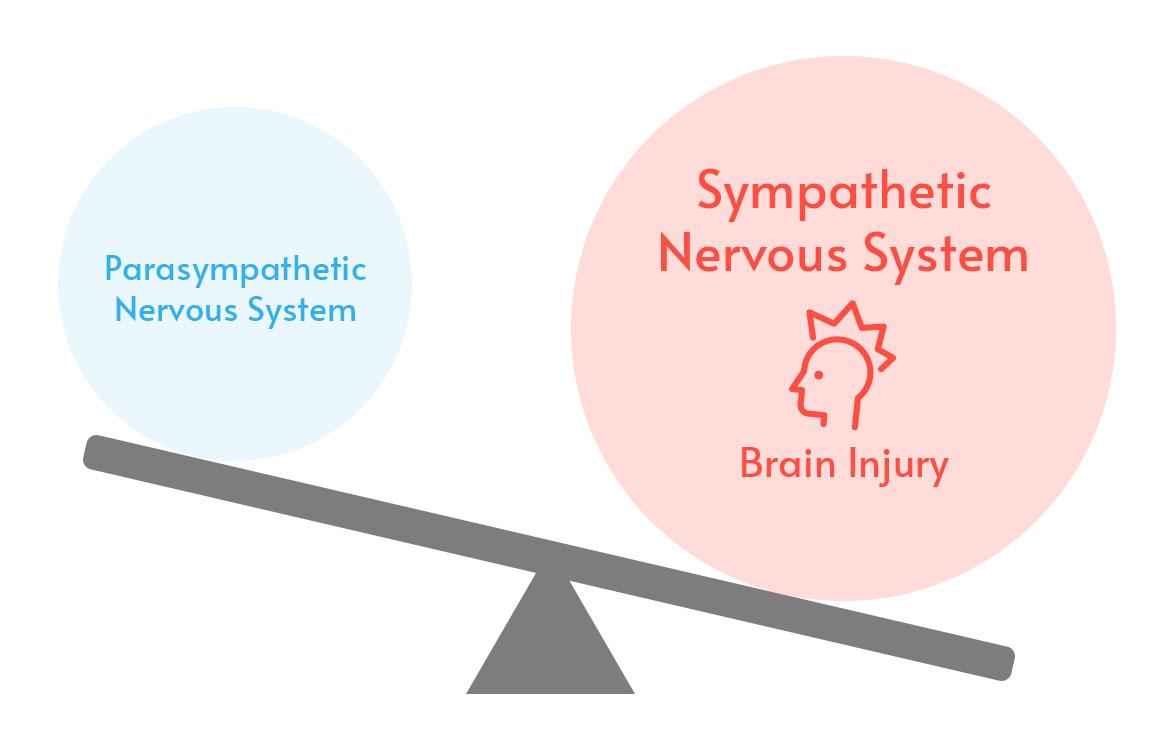

The physical trauma of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI, aka concussion) can cause temporary or long-lasting dysautonomia.

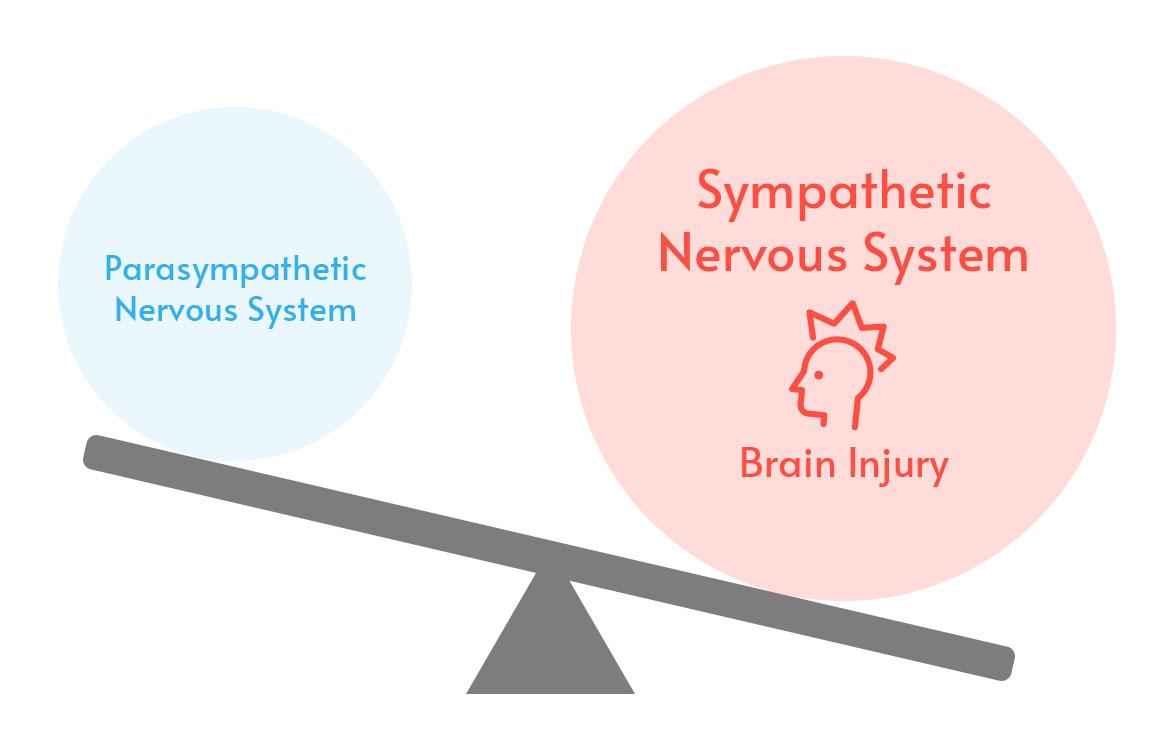

In concussion patients, dysautonomia almost always takes the form of sympathetic dominance. That means the sympathetic system, which puts your body on “high alert,” is more in control than it should be.

Giving the sympathetic nervous system more control is your body’s way of protecting itself. If the threat you were facing were a rampaging lion instead of head trauma, you’d definitely want the sympathetic system to be calling the shots! It facilitates quick reactions that can be life-saving in serious crises. Unfortunately, when that sympathetic dominance lingers after the traumatic event, it causes ongoing problems.

To make matters even more complicated, patients often exhibit symptoms of parasympathetic dominance in addition to sympathetic dominance. How does that make sense? As far as we know, the parasympathetic system can rebound temporarily, causing symptoms to fluctuate (for example, alternating between diarrhea and constipation). It’s like your nervous system swings too far to one side, and then the other, and then back again, pulling you on a whirlwind of unpleasant symptoms instead of reverting to the delicate balancing act typical of a healthy ANS.

To be honest, the medical community doesn’t fully understand why head injury induces lingering symptoms of dysautonomia. We have hypotheses and open areas of investigation, but it’s not a settled question.

Some current areas of investigation include:

- Dysregulation in two key brain regions: the insula and the anterior cingulate cortex. These regions are like the “Swiss Army knife” or the “crossroads” of the brain. They’re closely tied to ANS functioning and impact many systems through the brain and body.

- Dysregulation of the vestibular (balance) system. Exactly how the vestibular system works is another area of active investigation. The way that it ties into the brain and ANS could help us understand more about why some patients develop dysautonomia.

As we continue researching the topic and testing treatments, we’ll be able to improve treatment outcomes and further educate our patient community on steps they can take to manage or even resolve certain symptoms.

The Connection Between Post-Concussion Syndrome, POTS, and Neurocardiogenic Syncope (Vasovagal Syncope)

Some of the dysautonomic concussion patients we’ve treated were previously diagnosed with POTS or neurocardiogenic syncope (vasovagal syncope). These are autonomic conditions that doctors diagnose in response to blood pressure dysregulation.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is diagnosed when the patient experiences an increased heart rate upon standing. They may have a drop in blood pressure, fainting, and other related issues. They often also experience many other symptoms related to dysautonomia:

While patients of any gender or age can develop POTS, 80% of patients with the condition are females, primarily between the ages of 15 and 50.

Neurocardiogenic syncope is a loss of consciousness (or near-fainting and dizziness) caused by a sudden drop in blood flow to the brain. Each episode is often accompanied by other symptoms such as nausea, fatigue, brain fog, and general discomfort.

Both conditions have a few items in common:

- The diagnosis is a description of what is wrong with the patient but does not encompass the root cause of their symptoms.

- The symptoms experienced by the patient are all dysautonomic.

In other words, to get to the heart of the issue, it takes going beyond the diagnosis of POTS or syncope. Treatment outcomes are better when we understand the underlying issue causing these symptoms.

Not all cases of POTS or syncope are concussion related. But when they are, we’re able to better help patients with concussion-based dysautonomia by treating the underlying brain dysfunction from their injury. We can also give patients strategies to improve and manage their dysautonomic symptoms over time.

What Are the Treatment Options for Post Head-Injury Autonomic Complications?

Dysautonomia patients often see doctors who will treat one or two symptoms but not others. If they were aware of their head injury, their concussion management plan is simple: Stay at home and rest until the symptoms improve. Each symptom, if treated at all, is treated as an isolated issue rather than as a related cluster of symptoms.

At Cognitive FX, we use a multidisciplinary approach. It’s extremely important for patients with dysautonomia because everything is connected. If you fix one system but the others are still out of balance, it could pull the others more out of balance. It’s like turning gears: You can’t move one gear without moving all of them. So it’s best to get them moving all at once, in the way that you want.

Treatment at CFX is primarily designed to address brain dysfunction that hasn’t resolved after an injury.

We know that post-concussion patients suffer from poor neurovascular coupling (the connection between neurons and the blood vessels that supply them with nutrients). Each patient receives an fNCI brain scan that we use to pinpoint the specific areas of the brain experiencing neurovascular decoupling. After treatment, patients are re-scanned to confirm the progress they’ve made.

Treatment involves an intense combination of supervised aerobic exercise, cognitive therapy, neuromuscular/physical therapy, occupational therapy, sensorimotor therapy, and other exercises (like Dynavision).

The exact regimen is tailored to each person based on their medical history, symptoms, physical evaluations, and biomarkers identified in the fNCI scan.

One aspect of the treatment program which engages the autonomic nervous system is a cycle of exercise, cognitive effort, and rest.

You will prepare your brain and nervous system with supervised exercise (for instance, we have patients with dizziness and exercise intolerance use stationary bikes rather than a treadmill — for safety). This step is crucial because it increases cerebral blood flow and unleashes a cascade of neurochemicals that help your brain adapt and perform during the next phase. It also forces your brain and ANS to work together to supply the brain with the blood it needs.

You will prepare your brain and nervous system with supervised exercise (for instance, we have patients with dizziness and exercise intolerance use stationary bikes rather than a treadmill — for safety). This step is crucial because it increases cerebral blood flow and unleashes a cascade of neurochemicals that help your brain adapt and perform during the next phase. It also forces your brain and ANS to work together to supply the brain with the blood it needs.

The activate phase is when you complete most of your therapies. These are designed to force your brain and nervous system to adapt to increasingly difficult challenges.

Finally, the recover phase gives you a chance to destimulate and engage your parasympathetic nervous system before repeating the cycle. This helps your body relearn how to balance the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of your nervous system while giving your brain a chance to recuperate before the next round of therapy.

Patients also meet with a psychologist during their treatment week(s). If you have any psychological disorders (either pre-existing or mood changes that arose because of the injury), we will provide you with next steps and help you find the appropriate provider to continue recovery in your town of residence.

You can learn more about how our Enhanced Performance in Cognition (EPIC) Treatment program works here.

Note: We can’t emphasize enough that dysautonomia symptoms are not imagined. They are real, and they are difficult to handle alone. Because the human mind and body are so interconnected, and because the ANS is designed to respond to our psychological states, patients need to learn how their thought patterns influence their symptoms. It’s a feedback loop: If you’re worried about ANS symptoms, the mere fact of being anxious could help to trigger them. You’re not imagining them, but you also have to be mindful of how your psychological state can contribute to the symptom cycle.

Healing From Dysautonomia: A Lifelong Commitment

Our patients typically see significant improvement (on average, 77% based on symptom scale reporting and fNCI results) to many of their symptoms after treatment of their concussion-related symptoms. For the dysautonomic symptoms, however, recovery time varies more. Different patients come in with different levels of autonomic function. Patients with mild cases often recover quickly. Others recover after months of hard work. And some never fully recover but do experience lessening of symptom severity.

Even if you’re unable to make a full recovery, you can make progress. Patients who diligently do the “homework” we give them after treatment and who commit to a healthy lifestyle can continue improving for years after their visit to our clinic.

We don’t have a fail-proof cure for dysautonomia; no one does. But we’re committed to learning more. We’re actively researching ANS dysfunction and its treatment. And we’re eager to share our findings with our patients as we progress.

We hope you’ll include us in your recovery journey.

To learn more about how we can help you, schedule a consultation with our team.

You will prepare your brain and nervous system with supervised exercise (for instance, we have patients with dizziness and exercise intolerance use stationary bikes rather than a treadmill — for safety). This step is crucial because it increases cerebral blood flow and unleashes a cascade of neurochemicals that help your brain adapt and perform during the next phase. It also forces your brain and ANS to work together to supply the brain with the blood it needs.

You will prepare your brain and nervous system with supervised exercise (for instance, we have patients with dizziness and exercise intolerance use stationary bikes rather than a treadmill — for safety). This step is crucial because it increases cerebral blood flow and unleashes a cascade of neurochemicals that help your brain adapt and perform during the next phase. It also forces your brain and ANS to work together to supply the brain with the blood it needs.