What to Do When SSRIs Don’t Work

Even if an SSRI helped at first, you might find that its effects have faded—or perhaps it never worked for you at all. If you have major depressive disorder and this sounds familiar, you’re not alone.

Psychotherapy helps many people with depression — but it isn’t effective for everyone. For example, a large clinical trial found that nearly 60% of participants still met the criteria for major depression at the end of treatment, even if they experienced some improvement along the way.

There are many reasons this can happen: misdiagnosis, a therapeutic approach that doesn’t match your needs, underlying medical issues, or depression that’s resistant to standard treatments. But a lack of progress in one form of therapy doesn’t mean you’re out of options. Today, there are more evidence-based treatments for major depressive disorder than ever before — and many people only find relief after exploring several different forms of treatment for depression.

In this article, we’ll explain the common signs and reasons why therapy might not be working, the steps you can take to troubleshoot your treatment, and alternative options available if you’re not getting the results you hoped for.

We cover:

Talk therapy is an effective treatment for many people with depression, but not every person responds to every therapeutic approach. Because progress is often gradual — and because some emotional discomfort is expected — it can be difficult to determine whether therapy truly isn’t working or if you simply need more time.

Clinicians typically look for ongoing improvement in symptoms, functioning, and insight over weeks to months. If that isn’t happening, it may be a sign that the treatment needs to be adjusted. Here are five clinically relevant signs that therapy may not be working as well as it should:

Some sessions may feel repetitive, and therapy naturally has ups and downs. But over several weeks to a few months, you should see some movement — clearer understanding of patterns, symptom reduction, new skills, or improved daily functioning.

If you’re revisiting the same issues with no insight, change, or skill building, it may indicate a mismatch in the therapeutic approach.

Therapy can temporarily increase distress as you explore painful topics, which is normal. What’s not typical is feeling worse session after session with no sense of progress, clearer understanding, or stabilization in between. Persistent deterioration can signal that the approach or pacing needs adjustment.

It’s normal to feel hesitant before hard sessions. But ongoing dread, avoidance, or feeling unsafe or misunderstood by your therapist may indicate a poor therapeutic fit. You should feel supported, respected, and able to show up authentically — even when it’s challenging.

Effective therapy involves shared goals, measurable progress markers, and a sense of direction. If goals are vague, never revisited, or not connected to your daily challenges, it can feel like therapy is drifting rather than guiding change.

A good therapist will collaborate with you to define realistic goals and check in regularly on progress.

Therapy should leave you with practical skills: coping strategies, communication tools, behavioral changes, or new ways of understanding your thoughts and emotions. If sessions feel like unstructured venting without gaining skills or insights you can apply outside the room, the modality may not be the right one for you.

Psychotherapy may be less effective when the underlying condition isn’t accurately identified. Depression can overlap with — or be mistaken for — other mental health disorders such as bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, or substance use conditions. In some cases, medical issues like thyroid disorders, sleep disorders, chronic pain, or chronic fatigue can mimic or worsen depressive symptoms. When the diagnosis doesn’t fully capture what’s going on, the treatment plan may not target the right mechanisms.

Diagnostic challenges are especially common in primary care, where most people first seek help and where clinicians may have limited time or fewer tools to differentiate between overlapping psychiatric and medical conditions. Even among mental health specialists, distinguishing depression from related conditions (particularly bipolar spectrum disorders) can sometimes be difficult.

What to do: If you’ve been in therapy for a while without meaningful improvement, consider asking your therapist or doctor to revisit your diagnosis or conduct a more comprehensive evaluation. Clarifying the full picture can open the door to more appropriate and effective treatment options.

Modern neuroscience shows that depression rarely has a single cause. Instead, it emerges from an interaction of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Some people experience depression that is more strongly tied to brain-based changes — such as altered neurotransmitter signaling, inflammation, hormonal shifts, or disrupted neural circuits. Others develop depression primarily in response to life circumstances, chronic stress, trauma, or unhelpful thinking patterns.

Because depression has multiple potential drivers, treatment needs to align with the underlying contributors. For someone with more biologically rooted symptoms, a combination of therapy and medication (or other biologically informed treatments) may lead to better outcomes. In contrast, if depression is largely shaped by environment, cognition, or behavior, approaches like CBT, trauma-informed therapy, or lifestyle and social-support changes may be more effective. When the treatment doesn’t match the root contributors, progress can be slow or minimal — even if the therapy itself is high-quality.

What to do: If you feel therapy hasn’t been helping, bring this up with your therapist. Ask whether a different therapeutic approach — or an evaluation for biological contributors — might be appropriate. A good clinician will help you reassess what’s driving your symptoms and adjust your treatment plan accordingly.

If you’re not seeing meaningful progress in therapy — or if the structure of the sessions just isn’t working for you — you may not be in the type of therapy that best matches your needs. Different therapeutic approaches target different mechanisms, symptoms and skills. For example, some forms of psychotherapy are structured and skills-based (like CBT), while others focus more on insight, relationships, or past experiences.

For depression specifically, certain therapies — such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Behavioral Therapy (BT), and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) — have the strongest evidence base (read more on each of these here). If you’re receiving a type of psychotherapy that isn’t designed specifically for depression or hasn’t been well-studied and established as an effective treatment for depression, progress can be slower, inconsistent, or minimal. Even evidence-based therapies can fall short, however, if they don’t align with your symptoms, treatment goals, history, or learning style.

This doesn’t mean your therapy is “bad” — only that it might not be the right fit for you. Therapy is most effective when the approach matches the individual, and it’s completely normal to try more than one type of psychotherapy before finding the one that helps you improve.

What to do: Talk to your therapist or doctor about exploring a different therapeutic approach — one of the well-validated treatments for depression — that better aligns with your needs, preferences, and the way you naturally process information.

Therapy can also feel ineffective for people with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). TRD is typically defined as depression that does not meaningfully improve after trying at least two appropriate antidepressant medications. For some individuals in this group, psychotherapy alone may not be comprehensive enough, not because the psychotherapy is ineffective, but because the underlying biology of their depression requires additional specific intervention.

Psychotherapy is still an important part of a comprehensive treatment plan for TRD, but its benefits are often slower to appear and may be insufficient unless paired with a treatment that directly addresses the biological aspects of the condition. This can leave patients feeling frustrated or discouraged, even though the limited progress is not a reflection of their effort or the therapist’s skill — it’s simply a sign that more targeted interventions are needed.

What to do: If you’ve been diagnosed with TRD, talk to your doctor about whether adding or adjusting medication could help. As we’ll discuss later, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is also a well-supported option for people who haven’t responded to medications or psychotherapy alone.

If therapy isn’t helping, an underlying medical or psychiatric condition may be contributing to your symptoms. Depression often overlaps with other mental health disorders — such as PTSD, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, substance use, or intrusive suicidal thoughts — which can change how depression presents and how well certain therapies work.

Physical health conditions can also play a significant role. Issues such as thyroid disorders, chronic pain, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, heart disease, arthritis, epilepsy, asthma, or cancer can all worsen mood symptoms or create depression-like fatigue, sleep changes, or cognitive difficulties. When these conditions are active or untreated, psychotherapy alone may not lead to meaningful progress because the biological drivers of depression remain unaddressed.

Identifying and treating these underlying conditions is often essential for therapy to be effective.

What to do: If you have other medical or mental health conditions, talk with your healthcare provider about how they may be interacting with your depression. Medication may be part of the solution, but other options — such as collaborating with multiple specialists, adjusting the type of therapy, or adding group or skills-based treatment — can also help support better outcomes.

Establishing a healthy relationship with your therapist is crucial for getting the most out of treatment. This relationship should be nonjudgmental and with mutual respect, creating a safe space for patients to express themselves and share their concerns openly.

If you don’t trust your therapist or you feel uncomfortable around them, it will be very difficult for you to benefit from therapy. Perhaps the therapist doesn’t have experience with your issues, has different values, is culturally insensitive, or you simply clash with their personality.

What to do: Be honest with your therapist about how you feel about your relationship. If sessions don’t improve, don’t hesitate to explore new therapists who align more closely with your needs.

It’s also common for therapy to feel unhelpful when you’re experiencing internal resistance to change. Even when you genuinely want to get better, you may also feel uncertain, overwhelmed, or protective of coping patterns or beliefs. This can show up in ways that look like “therapy isn’t working” — missing appointments, holding back in sessions, or avoiding between-session homework or reflection. These behaviors aren’t failures; they’re signals that something in the process feels challenging or unsafe.

Resistance is a normal part of therapy, and noticing it is often the first step toward progress.

What to do: Recognize that discomfort is a natural part of growth. Bring these feelings into the open with your therapist — talking honestly about avoidance, fear, disagreement, or frustration allows you both to understand what’s getting in the way and work through it together.

Many people become discouraged with psychotherapy because they expect noticeable change to happen quickly. When progress feels slow or uneven, it’s easy to assume the therapy isn’t working. But meaningful recovery — especially from depression — often takes more time and patience than most people anticipate. Therapy involves understanding the roots of your symptoms, implementing new skills and behaviors, changing cognitive patterns, and practicing them consistently, all of which can sometimes unfold gradually.

Recognizing this pace can help you stay engaged rather than prematurely concluding that therapy has failed.

What to do: If progress feels slower than you hoped, bring this up with your therapist. Together, you can clarify what a realistic timeline might look like, adjust your goals, or modify the approach to better match your needs. Understanding the process can make therapy feel more purposeful — and more effective.

If you’re new to therapy, it’s easy to bring assumptions or misunderstandings into the process — and these can unintentionally get in the way of progress. Some people expect the therapist to “fix” their problems for them, not realizing that therapy is a collaborative process that requires active participation, effort, and change. Others may have had a negative experience with a past therapist and assume that all therapy will feel the same, which can limit openness and trust.

These misconceptions don’t mean anything is wrong with you — they’re simply beliefs that can shape how you show up in therapy and how much you benefit from it.

What to do: If you notice assumptions or doubts about therapy, talk them through with your therapist. Clarifying how therapy works — and what each of you is responsible for — can help reset expectations and make the therapeutic process much more effective.

If you’re new to psychotherapy, it’s often worth exploring potential adjustments before concluding that therapy isn’t right for you. Here are evidence-informed steps that clinicians commonly recommend:

If you feel stuck or notice a lack of progress, don’t stop therapy abruptly. Share your concerns openly with your therapist. They can clarify expectations, adjust the pace or structure, introduce new techniques, or help determine whether a different therapeutic approach may be more effective.

A consultation with another mental health professional — such as a psychologist, psychiatrist, or clinical social worker — can provide fresh insight into your symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options. Second opinions are common and can help identify issues that may have been overlooked.

A strong therapeutic alliance is one of the most reliable predictors of positive outcomes in therapy. If you feel misunderstood, unsafe, or unable to connect with your therapist despite trying to address the issue, it may be appropriate to switch to a different therapist whose style, training, or personality feels like a better fit.

If the modality you’re using isn’t effective for you, consider exploring different psychotherapy approaches. For example:

If CBT hasn’t helped with relational difficulties, Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) may be more suitable.

For chronic avoidance or emotion regulation difficulties, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) or Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) may be helpful.

Different therapies target different mechanisms of change, and it’s normal to try more than one before finding the best fit.

Lifestyle factors can meaningfully influence mood and treatment response. Regular exercise, adequate sleep, balanced nutrition, reduced alcohol use, and stress-management practices can complement psychotherapy and improve overall brain health. These changes are not a substitute for treatment but can enhance its effectiveness.

When psychotherapy alone is not providing sufficient relief, a clinician may recommend incorporating antidepressant medication, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which can help reduce symptom severity, stabilize mood, and make it easier to engage in therapy. Evidence suggests that combined treatment (therapy + depression medication) can be more effective and may reduce relapse rates compared to either approach alone for certain patients.

For people who don’t respond well to medication or have treatment-resistant depression, adding a brain stimulation therapy — such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), or other emerging neuromodulation options — may be appropriate. These treatments target the brain circuits involved in mood regulation and can significantly improve symptoms of depression, especially when other interventions have not worked.

In some cases — particularly when symptoms include psychosis, severe agitation, or treatment-resistant features — psychiatrists may consider augmentation strategies, which can include adding an antipsychotic medication or other agents. All medication or neuromodulation decisions should be made with a qualified prescriber who can tailor the treatment plan to your needs.

If you feel that you’re stuck and not making any progress, it may be time to consider alternative FDA-approved depression treatments.

We’ve written in-depth articles comparing TMS (the treatment we offer) to various alternatives, discussing their effectiveness, risks, side effects, and more. You can find those here:

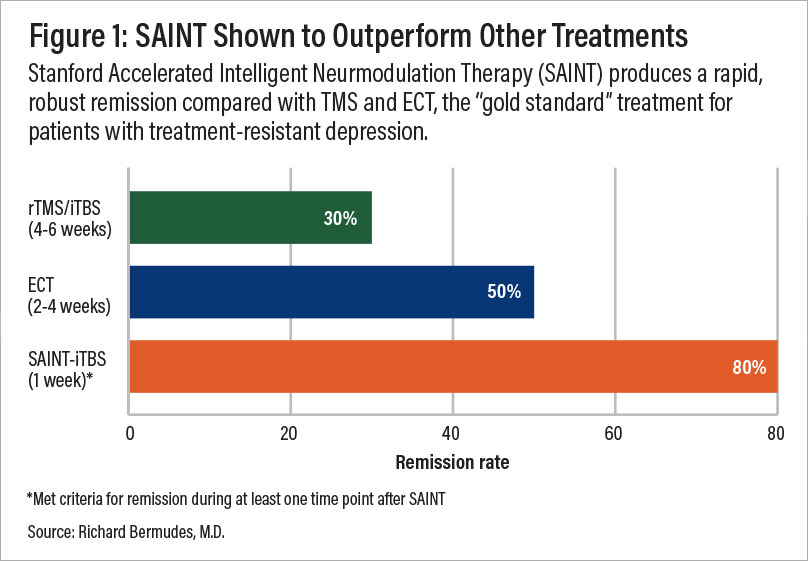

A comparison of remission rates for rTMS/iTBS, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and SAINT-iTBS.

Accelerated fMRI-guided TMS represents a major step forward in depression treatment. Unlike conventional TMS (repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation), which uses one-size-fits-all targeting and unfolds over four to six weeks, this approach uses brain imaging to precisely map each patient’s stimulation site and delivers multiple optimized sessions per day over just 5 days for faster, stronger results.

The original protocol, SAINT™ (Stanford Intelligent Accelerated Neuromodulation Therapy), has demonstrated remarkable success rates: in a double-blind controlled clinical trial, 85% of patients with treatment-resistant depression responded, and 78% achieved remission after just five days of treatment.

In addition to rapid symptom relief, accelerated fMRI TMS offers low risk and minimal side effects compared to medication, ECT, or ketamine. In short: it’s more personalized, more efficient, and often more effective — which is why it has become a compelling next-step option for patients who haven’t found success elsewhere. However, it remains costly ($30,000–$36,000) and difficult to access.

At our Utah-based clinic, Cognitive FX, we offer accelerated fMRI-guided TMS that combines the core strengths of SAINT—precision targeting and an accelerated treatment schedule—without the $30,000+ price tag.

Key differences between our treatment and Magnus SAINT™ TMS include:

We use advanced fMRI analysis by our neuroscientist and physician, rather than proprietary software, to determine the stimulation site.

We process scans in-house, leveraging 25 years of clinical fMRI experience from treating brain injury patients.

We pass those efficiencies on to patients: $9,000–$12,000 vs. $30,000+.

| Accelerated fMRI - TMS | Magnus SAINT™ TMS | |

|---|---|---|

| FDA-Approved iTBS | ✔ | ✔ |

| FDA-Approved Neuronavigators | ✔ | ✔ |

| FDA-Approved Figure 8 Coils | ✔ | ✔ |

| Number of Treatment Days | 5 | 5 |

| Treatments per Day | 10 | 10 |

| Total Treatments | 50 | 50 |

| Number of TMS Pulses | Approx. 90,000 | 90,000 |

| Resting motor threshold pulse intensity | 90–120% | 90–120% |

| FDA-Approved Personalized DLPFC Targeting | ✘ | ✔ |

| Personalized DLPFC Targeting Assists Doctor in Target Location | ✔ | ✘ |

| Personalized E Field Coil orientation | ✔ | ✘ |

| Cost | $9,000 to $12,000 | $30,000+ |

Of all the types of TMS available, this is the most targeted, safe, and effective protocol for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

To improve outcomes for our patients, we also include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as a part of our treatment. When combined with the traditional method of TMS (rTMS), CBT improved response and remission rates by ~8% and ~19%, respectively. Additionally, CBT is likely to produce sustained improvement over time once treatment has concluded.

Our personalized treatment is ideal for most patients with treatment-resistant depression. However, we do not treat patients under the age of 18 or over 65. Additionally, as a safety measure, we do not treat patients who have a history of seizures or who are currently actively suicidal and in need of crisis care.

Click here to learn more about receiving accelerated fMRI TMS therapy at Cognitive FX or take our quiz to see if you’re a good fit for treatment.

If you’re unfamiliar with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and its different variations and want to learn more, the following articles are a good place to start:

Dr. Spangler is a Clinical Psychologist with over 20 years of experience working in both clinical and academic settings. She earned her doctorate degree in Clinical Psychology at the University of Oregon followed by a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in the Department of Psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Spangler served as a Professor of Psychology at Brigham Young University for 15 years where she directed training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Clinical Psychology Doctoral Program, and conducted research on the etiology and treatment of depressive, anxiety, and eating disorders. She also served as a Visiting Professor in the Department of Psychiatry Cognitive Therapy Centre at Oxford University in England. Dr Spangler has authored over 60 publications and has lectured worldwide. She has received numerous awards for her collective work from the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Psychological Association, the International Association for Cognitive Psychotherapy, the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, the Beck Institute, and the National Association of Professional Women.

Even if an SSRI helped at first, you might find that its effects have faded—or perhaps it never worked for you at all. If you have major depressive disorder and this sounds familiar, you’re not alone.

To understand why your depressive symptoms aren’t going away, it’s important first to recognize that major depression is a complex disorder influenced by various factors. Effective treatment requires...

If you’re wondering what to do when transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) doesn’t work, you might be:

In 2022, a reanalysis of the largest antidepressant study ever conducted found that traditional antidepressant medications only relieve depression symptoms in about one-third of patients who take...

Clinics across the U.S. now offer TMS therapy specifically for anxiety. While early research suggests TMS may be an effective treatment, only a handful of studies have focused exclusively on anxiety.

Traditional antidepressant medications involve a trial period of weeks or months before it can be determined whether or not they are working. If a medication doesn’t work — and it’s been shown that ...