How to Find a Post-Concussion Syndrome Support Group | Cognitive FX

Post-concussion syndrome is an “invisible” illness.

Published peer-reviewed research shows that Cognitive FX treatment leads to meaningful symptom reduction in post-concussion symptoms for 77% of study participants. Cognitive FX is the only PCS clinic with third-party validated treatment outcomes.

READ FULL STUDY

If someone you love breaks their wrist, it’s easy to know what’s next. A doctor will tell you how long the injury needs to heal, what to do, and what not to do. Helping out could mean braiding hair or carrying books. While it’s not a fun experience for anyone involved (and you might tire of being on dish duty every night), there’s always an end in sight. No one struggles to understand why they’re in pain from a broken wrist.

Brain injuries are different. You can’t see the injury. You have so many questions: How long will recovery take? Will they ever be the same as they were before the injury? Which symptoms are from the brain injury and which are medication side effects? Meanwhile, your loved one may have a hard time putting their feelings and pain into words. Their experience is so much more than just saying “It hurts.”

Unlike with a broken bone, there’s no neat and tidy formula for recovery; it looks different for each person. It’s hard on the patient and it’s hard on the people around them who don’t know when, if, or how long it will take to recover. With a broken wrist there is a timeline. A broken bone doesn’t cause mood swings, emotional outbursts, inability to focus, memory struggles and so many other confusing symptoms like concussions do.

It’s OK to grieve after someone you love sustains a life-changing injury. It’s OK to be frustrated by the uncertainty of it all. If you’re grappling with these emotions and wondering what you can do to help your loved one get better, this guide is for you. We cover:

The first section of this post gives you resources to understand the injury itself and how to handle specific scenarios and symptoms arising from that injury. Afterward, we dive into what you can do as a caregiver or friend of someone with a traumatic brain injury.

If you or a loved one are suffering from lingering symptoms after a traumatic brain injury, you’re not alone. We can help. 95% of our patients experience statistically verified restoration of brain function. Their symptoms improve, on average, by 75% in just one week. Book a consultation with our team to learn if you are eligible for treatment.

Note: Any data relating to brain function mentioned in this post is from our first generation fNCI scans. Gen 1 scans compared activation in various regions of the brain with a control database of healthy brains. Our clinic is now rolling out second-generation fNCI which looks both at the activation of individual brain regions and at the connections between brain regions. Results are interpreted and reported differently for Gen 2 than for Gen 1; reports will not look the same if you come into the clinic for treatment.

One key to understanding how to help your loved one after a brain injury is learning about what they’re going through. Some patients have a hard time putting into words what symptoms they are experiencing. Having a better understanding of brain injury and its effects can help you empathize more fully and know what they need. But that can be difficult when so many myths about concussion and traumatic brain injuries persist. Here are some examples:

Myth: The best way to recover from a mild traumatic brain injury is to stay in a dark room and rest.

Fact: An active recovery is better. Patients who try some physical activity (to the extent that they can) and do cognitive exercises in addition to resting recover better and faster.

Myth: Symptoms of a concussion go away after two weeks.

Fact: While most mild TBI patients recover within two weeks, some take longer. Up to 30% of people who sustain a concussion have symptoms that linger for months or years after their injury (a condition known as post-concussion syndrome). This happens when the patient’s neurons don’t communicate efficiently with the blood vessels that supply them with energy, a process called neurovascular coupling.

Myth: You have to experience loss of consciousness to get a mild traumatic brain injury.

Fact: Concussions can come from a blow to the head, whiplash, or jostling of the brain. You don’t have to lose consciousness. Concussion-like illness can also come from other circumstances, such as carbon monoxide poisoning, bacterial and viral disease, chemotherapy, mini-strokes, and more.

Myth: Severe traumatic brain injury symptoms will never get better after initial rehab.

Fact: We believe recovery is life long. Why? Because we’ve seen it. And because the brain’s neuroplasticity allows it to keep adjusting to your injury. While their brain may never make a full recovery, they can keep making progress, even if they’ve sustained some irreparable brain damage.

While we can’t tackle everything you need to know about traumatic brain injury in one post, we can point you to helpful resources for patients and their families. Here are some posts that walk through the basics:

This post is not a comprehensive list of every action you can take to help your loved one after their injury, but it does include some of the most impactful practices you can embrace.

Here’s what to do after your loved one comes home from the emergency room or doctor’s office and settles in (not in order of importance):

Keep in mind that your role may shift as they move through the recovery process. An acute concussion recovery might only take two weeks, whereas post-concussion syndrome may continue indefinitely until treated. Severe traumatic brain injury patients may need help with basic tasks such as bathing and eating at first, or they might only need help in key symptom areas (like memory). The severity of the injury, the type of injury, and their treatment regimen greatly impact their recovery journey; how you take care of them will have to adapt to their needs and progress.

Further reading: Five severe TBI recovery stories

Note: This post is not meant to replace a doctor’s medical advice. In case of a conflict, follow the treating health care provider’s instructions first. If you have questions about post-concussion syndrome treatment and recovery, you can reach out to our team.

After a brain injury, the normal daily activities your loved one used to do easily may suddenly have become overwhelming. A simple trip to the grocery store might now be an incomprehensible maze filled with glaring lights and the distress of forgetting what they came for. But that doesn’t mean they can’t attempt to do the shopping, or the cleaning, or their work. Instead, they may need some help breaking down an activity into manageable pieces.

For example, if they want to do the grocery shopping, help them break it down into smaller tasks, like this:

Note: Depending on the severity of their injury, cooking and driving may be too ambitious. Talk to their physician about which goals are achievable, respect their wishes, and help them do whatever they’re motivated to attempt (safely).

If their goal is to clean the kitchen, perhaps you encourage them to start by loading the dishwasher, then wiping counters, then taking a break before cleaning the floors or taking out the trash, and so forth. Whatever they need to do, help them do it piece by piece so that they aren’t just getting frustrated and giving up when they start to feel overwhelmed.

Bright or fluorescent lights, loud noises, crowded or visually busy spaces, and conversations with more than one person at a time are all common triggers of overwhelm in mild to severe TBI patients. Learn what causes your loved one distress, learn their limits, and help them stay engaged up to that point. After that, you might need to help them disengage and recharge.

For example, let’s say you’re planning to go to Costco and your spouse has a brain injury. You know the crowds and the lights will bother your spouse. Instead of leaving them at home, bring them to the store, but don’t dawdle. No chatting with the couple you know from church or wandering down the aisles with gadgets you need. Go in, get the items on your list, and get out before your spouse gets overwhelmed. If they can’t handle a whole Costco trip, you could get them a snack at the food bar and then let them retreat to the car when they’re tired.

Another example is driving. For patients with certain vestibular or visual symptoms, either driving or being a passenger could trigger symptoms. For some, driving is more comfortable than being a passenger. For others, being a passenger is much easier than driving. Learn which one is best for your loved one and let them do that.

Some exposure to triggers is good. It will aid their recovery. But the goal is not to push them into a state of overwhelm or to make them do anything they’re not ready to do.

After a brain injury, it’s easy for patients to get overwhelmed. Their brain simply can’t handle all the stimuli it used to. For some people, getting overwhelmed leads to angry outbursts or tears of frustration. Others become withdrawn and seek escape.

Some signs of overwhelm include getting a glazed over or glassy-eyed look, difficulty expressing themselves, withdrawing from conversation, and mounting frustration.

Learn the warning signs of overwhelm in your loved one so you can intervene when they need it. Make sure they always have a quiet, safe space to retreat to. For example, if you have guests over or are visiting friends, set aside a dark, quiet room exclusively for your loved one to use. If they start getting overwhelmed, they can retreat to that space to breathe it out and return when they’re feeling better.

Socializing after a brain injury is hard, but it’s still important for you both to spend time with friends — even during the coronavirus pandemic, as long as you are following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (see cdc.gov) guidelines for interacting safely. If dinner and a board game is too much, consider alternatives, such as a lunch date. It’s shorter and therefore requires less stamina.

You can make small changes around the house to make it a safer, less stressful environment for your loved one.

If they have any issues with balance or gait after their injury, it’s time to declutter. Keep all the major pathways clear of toys (be they for kids or pets), boxes, and other objects. If you have rugs, consider rolling them up for now — they are a tripping hazard.

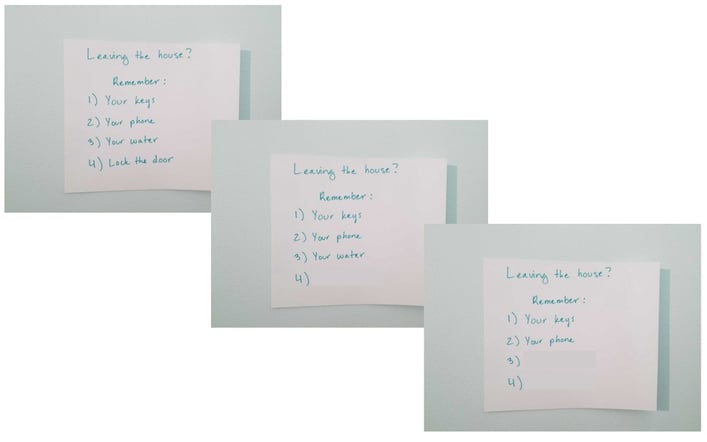

If they have short-term memory problems, make little signs to help them out at first. For example, you can make a sign for the door that has the main items they need (e.g., keys, water bottle, wallet). To help them exercise their memory, gradually reduce the number of items on the list so they have to think through what the missing items were.

Monitor their key spaces — the desk, the bedroom, and any other spaces where they spend a lot of time. Help them keep everything organized in those areas so that it a) stays consistent and b) makes them happy. Doing so will help them find what they need and feel safe, which lowers their stress levels and aids recovery.

If they have light sensitivity, encourage them to spend time in family rooms by dimming the lights. If you don’t have a dimmer switch, try removing some light bulbs (but not all of them) or covering lamps with a translucent material (keep an eye on their temperature and don’t leave them indefinitely as this could pose a fire hazard).

If they want to spend time on the computer, smartphone, or TV, get them blue light filtering glasses. This will help reduce headaches and eye strain from screen time. If they’re holding an electronic device really close to their face, try to coax them into moving the screen further away.

Keeping a consistent daily routine helps, too. It will decrease their stress and help them become more self-sufficient as they improve.

Brain injury patients aren’t always eager to leave their safe spaces. Some patients will stay locked in a dark room for days on end. While you shouldn’t try to force them out, you can encourage them to make progress.

Invite them on a short walk around the block with you. They may need to wear sunglasses, or take advantage of a cloudy day. Exercise is great for the brain!

See if they’ll let you open the shades just a tiny bit; maybe you can slowly increase the light in that room.

If they can’t handle conversations well, have just one friend over at a time instead of three. Or perhaps you can start with 20-minute social visits that slowly increase in length.

The key is not to be forceful. Instead, be encouraging, and take care of the little details so it’s easier for them to say yes. If they say no, try again another day.

Some brain injury patients are able to do quite a lot; others can do very little. It all depends on the severity of their symptoms. If you’re their caregiver (or a good friend looking to help out), then you will likely have to take over some chores and other obligations for them.

If they were the family caregiver in charge of the schedule, for example, you may have to get a shared wall calendar to get that responsibility off their plate. If they struggle with driving, someone else needs to handle that, whether it’s getting them to follow-up medical care appointments or driving the kids to soccer practice. If you can’t do it, find someone who can.

However you divvy up the work, make sure your loved one is a part of the conversation. Don’t forcibly take tasks from them unless it’s a safety issue. Instead, ask what they’d like help with and talk to them about how it needs to be done. Let them be a part of what’s happening, even if they can’t do it the way they did before.

Patients need extra support while going through treatment. Here’s what we recommend family and friends help with when patients get treatment at our clinic:

We love to see friends and family get involved and help their loved ones through treatment! That said, we do recommend against observing cognitive and physical therapy sessions. Sometimes family members need to be present (for example, if you need to translate or are learning the therapy technique to keep doing it with them at home). But most people actually make more progress in therapy when their family members aren’t watching. It takes some pressure off, and it removes the possibility of you stepping in to help, which they might have grown used to.

These two behaviors are easy to fall into, but they’re not good for you or for the patient.

It’s tempting to step in and do whatever needs doing, especially when you see your loved one struggling. But that struggle is actually key to their recovery: They need to get practice doing things that are hard. Their brain needs as much problem solving practice as it can get without overloading.

So the next time you’re out for a meal, don’t order for them. Let them do it (or help them through it) rather than speaking on their behalf. When a friend asks them a question, let them answer. When they’re trying to fix a snack, let them. Give them some autonomy.

If they try and fail, then you can step in. But the brain learns from that attempt, even if they fail. It’s an important part of the recovery process. As difficult as it may be to watch from the sidelines, you are helping them immensely by letting them fail sometimes.

If you drop a plate and they scream at you, it’s not because you did something terrible; it’s that the noise triggered their autonomic nervous system and made them panic, leading to an exaggerated response.

Mood swings and irritability hurt both patients and their caregivers. They’re not trying to make your life hard. Many patients are distraught at the lack of emotional control they have after an injury. Unfortunately, a brain injury makes it a) easier to trigger an emotional reaction and b) harder for them to keep those emotions under control. Their brains are dealing with too much. Brain injury can take a severe toll on mental health.

We highly recommend therapy for family members as well as for the injured person. Your loved one can learn breathing and mindfulness practices to help with outbursts, but in the meantime, find someone you can vent to, or locate a support group with other caregivers like you. Everyone can benefit from some emotional support.

If you have children who are affected by these changes, sit down with them and explain that their family member’s brain is not the same as before and that it needs a little more time to calm down. You might be surprised by how much that knowledge helps them cope — it’s usually a huge relief for them to understand that their family member’s extreme emotional reactions are not their fault.

Caregiver burnout is a state of exhaustion (physical, mental, and emotional) accompanied by a change in attitude toward the patient. If you’re suffering from burnout, you might notice that you used to be concerned and caring, but now you feel resentment toward the patient for being so needy.

Caregiver burnout is especially common when a traumatic brain injury is involved. Depending on the injury severity, caregiving can be a lot of work. Meanwhile, you still have to deal with the grief and uncertainty of wondering how much they will recover and how long it will take. Since TBI often comes with emotional changes, you may be on the receiving end of their frustration or sadness (whether or not they mean you to be).

If you have caregiver burnout, it does not mean that you are a bad person! It actually makes you very normal. It just means you need to take a step back and care for yourself before you can offer care to someone else.

These practices are all key to stave off burnout:

Admittedly, these practices are easier said than done. Traumatic brain injury can bring huge shifts in responsibility and financial well being. You might be down one income, or be juggling a full-time job and caregiving.

If you feel like there’s no way to take care of yourself and the injured person, that’s a problem! But you can solve that problem. Break out some pen & paper (and the calendar) and make a list of what you’re doing and what you need to do. Make a schedule. Figure out what you have to do versus tasks you can hand off to family members and friends.

See if you’re doing something that the patient could actually do for themselves; often, caregivers do more than they have to just because they feel like they should. Make a plan you can actually follow instead of one that leaves you in tears because you can’t keep up.

If you find yourself burned out, it is so important to step back and rest. Find a temporary, alternate caregiver (or permanently, if need be), and nurse yourself back to health. You can’t give what you don’t have — nor should you have to.

Brain injury is an “invisible” illness. We can’t see what’s wrong, but it is so hard on both patients and their loved ones. It’s OK to grieve the past and be uncertain about the future. You’re allowed to get frustrated and work through difficult emotions.

The way things are now is not how they’ll be forever. The brain is an amazing organ that can regain some or all of its function through neuroplasticity. This doesn’t mean there won’t be bumps in the road. Illness (from the common cold to COVID) and other sources of physical distress can set back their recovery timeline.

We understand that when a person suffers from a head injury, the people around them suffer too. We have seen the struggle and the emotional roller coasters that support people face. You are not alone in this. Just keep doing your best to support your loved one in their recovery. It’s a difficult road, but they will make more progress with your help!

If you or a loved one are suffering from lingering symptoms after a traumatic brain injury, you’re not alone. We can help. 95% of our patients experience statistically verified restoration of brain function. Their symptoms improve, on average, by 75% in just one week. Book a consultation with our team to learn if you are eligible for treatment.

Kathryn ‘Kaydee’ Severs is a Registered Nurse. She started her nursing career serving in the US Army Reserves as a combat medic. During her time in the Army she was certified as a Emergency Medical Technician and a Licensed Practice Nurse. Kaydee worked as an LPN in California, Utah, and Colorado and continued her serve her country in the Army Reserve. In 2005 she was deployed to Germany to work in the ICU at Landstuhl Regional Medial Center. This is where she met her husband Eric. He was active duty in the Air Force. Since then they have been stationed in Colorado, Utah, and Mississippi. Eric went on two more deployments and Kaydee continued her schooling to receive her RN. Their greatest achievement are their four amazing children. As an RN Kaydee has worked as an ER nurse in Colorado Springs and at the University of Utah. In Mississippi she worked as a pediatric nurse for medically fragile children. Kaydee is excited to be a part of the health care team at Cognitive FX. She has had many friends and family who have suffered from TBI’s and it pained her knowing she couldn’t ease their symptoms. This amazing program and the staff have given her the tools and training to help do just that!

Post-concussion syndrome is an “invisible” illness.

Have you ever gotten stuck in a task, set it aside for a while, and then discovered that it somehow seemed easy when you came back to it? If so, you’ve experienced the power of strategic breaks to...

Quirien Willemsen is a happy, busy mother to three young girls in Loenen aan de Vecht, The Netherlands. She works as a legal counsel for a bank, loves going skiing on holiday, and embraces life to...

When Sam Pembleton arrived at Cognitive FX for post-concussion syndrome treatment, she was shaking. Her nerves were so bad that she couldn’t speak to the other people in the waiting room. When they...

Many people are surprised to learn that concussions can have long-term effects if left untreated. Chronic concussion syndrome is a less common term for persistent post-concussion symptoms (also known...

[Note: This article was written during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. We recommend that you check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for travel advisories and health...

Published peer-reviewed research shows that Cognitive FX treatment leads to meaningful symptom reduction in post-concussion symptoms for 77% of study participants. Cognitive FX is the only PCS clinic with third-party validated treatment outcomes.

READ FULL STUDY